Highlights

-

Qualitative analysis revealed that clients’ and therapists’ perspectives on what makes a therapy room are divergent and require adaptive spaces.

-

The structural elements of a therapy room should promote privacy and comfortability.

-

Focus point emerged as a key finding that may support therapeutic grounding. Further research that identifies what constitutes a focus point within a therapy room may be useful.

INTRODUCTION

The late 1970s witnessed a significant shift in the attention of researchers from human behaviour alone to the relationship between the built environment and human behaviour. According to Prochansky, “the physical environment we build is as much social as physical. The built world … a school, a hospital, a house, or a highway is simply the specific expression of a social system which generally influences our activities and our relations with others” (Proshansky et al., 1976, p. 8).

In recent years, however, with the advances in architectural design and engineering and increased interest in psychotherapy, more efforts are being made to study the built environment’s impact on therapeutic engagements and outcomes. Research findings have examined the effects of room design, key elements, and layout on aspects of therapeutic engagement such as personal disclosure and communication (Okken et al., 2013), perception of the therapist (Backhaus, 2008), and of the environment for therapy (Ornstein, 1986). Several studies have investigated how clients perceive the therapy environment to impact the therapy process (e.g., Anthony & Watkins, 2002) and how the therapists’ perception of their work environment affects their therapeutic engagement, relationship, and process. Anthony and Watkins (2002) usefully outline how the physical environment impacts psychological processes both within and outside the therapy room and highlight that the physical environment may influence the attitudes and behaviours of therapists and clients. The therapist who utilises the room as a work environment where therapy is delivered and the clients who visit the therapist within the designated room where they would receive therapy now become the immediate stakeholders. This raises the question of what constitutes an ideal therapy room, including its design’s structural aspects and the dynamic and interpretative processes from the perspectives of these main stakeholders.

Elements of a Therapeutic Room

Research examining the impact of the environment on different health and well-being outcomes has provided insight into elements that are deemed necessary in a typical therapeutic environment (For example, Pearson & Wilson, 2012; Phelps et al., 2008; Rapoport, 1982/1990; Sanders & Lehmann, 2019, and Gharaveis & Kazem-Zadeh, 2018). Rapoport (1982/1990) described these physical elements as communicating non-verbally to the built environment users, for example, relaxing comfortability feelings (nature and position of furniture). The nature of the room, including its size and colour, lighting, decorations, room temperature, noise levels, cleanliness, openness, and tidiness, were all regarded as communicating non-verbally to the room users. Furthermore, the external environment of the therapeutic room has also been indicated as essential (Phelps et al., 2008; Weeks, 2004). For example, a welcoming entry where service users could anonymously seek help and participate in a range of designated positive and developmental programmes will appeal more to them than an entry to the waiting room with security personnel standing on guard (Jones, 2020; Weeks, 2004). The physical environment of a room gives cues about its purpose, capabilities, and qualities (Rapoport, 1982/1990), thus setting expectations from the first point of contact. Although it has been long ago, Rapoport’s (1982/1990) interesting findings from participants recruited from the general population emphasized the heavy load of affective and meanings that people use to describe environmental elements to identify the purpose of a room and its characteristics. Other findings also suggested that a therapy environment and its elements play a role in welcoming clients and ensuring their comfort throughout the therapeutic process (Backhaus, 2008; McElroy et al., 1983).

Due to the divergent meanings people associate with the objects in the environment, reactions to them will also vary (Jones, 2020; Rapoport, 1982/1990). Research has described both therapist and client preferences for these elements, with researchers making suggestions of what is deemed best (Devlin et al., 2009; Dijkstra et al., 2008; Larsen et al., 1998; Pressly & Heesacker, 2001). For instance, Pressley & Heesacker (2001) described the physical elements that may enhance or distract from a counselling process as the therapy room that the client perceives as warm and has an intimate room design, with cool hues and low intensity, because this allows clients to be relaxed and leads to better self-disclosure. This finding aligns with other researchers’ observations that spatial changes to a therapy room resulted in users’ reports of better satisfaction, comfort, and improved interactions with the therapist and other clients (Goelitz & Stewart-Kahn, 2008; Jones, 2020). Building upon the view that people differ in their sensitivity to environmental stimuli, Dijkstra, Pieterse and Pruyn (2008) suggested that white walls aggravate the feeling of stress for those with ‘low screening ability’ while green appears to have stress-reducing effects and orange producing arousal effects. Another researcher earlier noted that hard, impervious architectural design tended to distance people from the environment and others (Sommer, 1974). However, although the therapeutic room remains consistent, accessories have been promoted to create comfort while also operating as a form of therapist disclosure (McElroy et al., 1983). Other findings have expanded upon location, image, privacy, degree of visibility, the proximity of restrooms, easy-to-read clocks, separate entrances and exits, furniture, lighting, views, plants, and artwork, as well as what makes a good therapeutic setting (Anthony & Watkins, 2002; Pressly & Heesacker, 2001; Weeks, 2004). Recent research has addressed the importance of trauma-informed design with adaptable physical environments that promote a sense of calm, safety, dignity, empowerment, and well-being (Sweeney et al., 2022).

Client Perception of Therapy Rooms

Backhaus (2008) found that accessories, furniture, colour, sound, room design, and lighting impact the therapeutic relationship and outcomes. Moreover, cleanliness is ideal for creating a welcoming and comfortable space (McElroy et al., 1983), while lighting has been associated with the perceived trustworthiness of the therapist (Backhaus, 2008). It was, however, further established that while clients rated furnishing as more critical, lighting was rated as more important by therapists. According to Fraser and Solovey (2007), office accessories impact clients’ perception of the therapist. Furthermore, Anthony and Watkins (2002) address how the environment and the client interact with objects sometimes triggering emotional memories that become relevant to the therapeutic endeavor. In a mixed-methods study conducted by Sinclair (2020), the author reported that comfortable seating and room temperature, soundproofing, no interruptions, and room accessibility were identified as the most critical aspects of the physical space to clients and therapists. The qualitative themes further showed that the participants reported ‘comfort,’ ‘the appearance and meaning of the room,’ and ‘the room as a workspace’ as what they considered helpful. Sanders & Lehmann (2019) also explored clients’ experiences and preferences for counselling room space and design and found that the primary motivation for clients’ design preferences was the desire for a sense of physical and emotional comfort, which was achieved by creating a welcoming, relaxed and homely environment that promoted a sense of safety and security. Though the existing research identifies commonality about client preferences, varying abilities to screen out aspects of the environment perceived as distracting or less than ideal has been found to impact mood and creativity (Martens, 2011). Flexibility may, therefore, be important in accommodating the needs of clients and therapists.

Therapists’ Perception of Therapy Rooms

Research by Backhaus (2008) showed differences between the perception of clients and therapists’ perception of a therapy room. Therapists were found to rate objects as being more important than clients. Furthermore, accessories were given more importance by those who did not design their own office spaces and, henceforth, aimed to create a welcoming environment in other ways. This finding has been supported by a recent study among clinical psychologists (Punzi & Singer, 2018). Therapists were reported to place importance on minimal distractions, with clutter and distracting sounds within the building considered a negative attribute. These findings highlight that therapists place greater overall importance on the physical environment for therapy than clients with sound viewed as most important, followed by room design, lighting, temperature, and furniture. Accessories and colour were considered of the least importance. Therapist perspectives on what makes an ideal therapeutic room are further informed by theoretical perspectives on therapeutic boundaries and what constitutes the ‘therapeutic frame.’ Within a psychodynamic approach, the space in which therapy takes place is an essential aspect of the therapeutic frame, through which a reliable and professional relationship enables reflection on old patterns and the working through of unconscious processes. This approach can be contrasted with more contemporary perspectives on outdoor therapy that encourage the movement of therapy outside of the therapeutic room allowing for the integration of behaviorally focused interventions and eco-therapy principles (Revell et al., 2014)

Design of Mental Health Care Settings

Health professionals regard the built environment for mental health care as having a considerable influence on treatment outcomes, experiences, and perceptions of care (Broadbent et al., 2014; Oeljeklaus et al., 2022). Studies in mental health settings show that inpatient, community, and day treatment settings are important (Oeljeklaus et al., 2022; Wilson et al., 2023). Evaluations of specific design interventions have shown that good design of therapeutic environments leads to better clinical outcomes and less stress for the users, both patients and staff (Berry et al., 2004; Marberry, 2006; Ulrich, 2006). Drawing upon environmental psychology, the works of Ulrich have been influential in arguing for environments that prevent/reduce stress. Ulrich identified healing gardens, views of nature, and legible building plans and signage as design features that contribute to positive psychological and physiological health (Ulrich, 1999; Ulrich et al., 2003) and these features are increasingly integrated within health and educational settings (Lau et al., 2014; Sherman et al., 2005). Following the systemic review of 13 qualitative studies that focus on the health effects of the physical environment for mental health patients, Oeljeklaus et al. (2022) identified three superordinate themes to describe the health effects of the physical environment for mental health patients. The space’s physical, social, and symbolic dimensions are shown to incorporate perceptions of comfort, efficacy, and a sense of safety that encourages meaningful activity and social connection for those receiving mental health care. Moreover, therapeutic landscapes have been shown to promote the maintenance of physical, procedural, and relational security for patients and those who deliver care (Wilson et al., 2023). Specifically, Wilson et al. (2023) showed that the built environment should promote physical security and support meaningful interactions between service users while enhancing efficient workflow for mental health care delivery. A purposeful design was shown to be beneficial in accommodating access to spaces that are suitable for group activities, interaction with families, and opportunities for patients to relax and disengage from others when needed.

Environment and Emotional Disclosure, Comfort and Flexibility

Emotional disclosure, comfort, and flexibility are central to developing a responsive therapeutic alliance, yet studies examining the environment’s interaction with such processes remain limited. Empirical studies examining the impact of the built environment upon communication and disclosure have conveyed varied results with the impact of environmental factors such as spaciousness and lighting depending upon individual perceptions and the topic and nature of the discussion (Haase & DiMattia, 1976; Lecomte et al., 1981). Regarding spaciousness, Lecomte et al. (1981) highlight that the intermediate distance (127cm) between counselor and client enhanced communications and client self-disclosure. Moreover, the research has highlighted the need for adjustment to accommodate client and therapist comfortability with seating arrangements changing following the development of a therapeutic alliance (Broekmann & Moller, 1973). Research observing nonverbal impact identified the importance of room to move in supporting self-disclosure. Okken et al. (2012, 2013) showed that the effect of room size of self-disclosure changes considerably, depending upon the topic, with decreasing personal space hampering discussion of topics of a more personal nature. The study findings highlighted the fact that personal space intrusions were managed using readjustments to posture and eye contact in order to moderate interpersonal closeness (Okken et al., 2013). Given the importance of personal disclosure and readiness to communicate within the talking therapies, further research exploring the perception and impact of spatial considerations within the built environment is essential. Given the varied and dynamic interaction between psychological and spatial aspects of the built environment within therapeutic encounters, research is needed to explore the various contributions of therapists and clients in constructing the ideal space.

Summary

The reviewed literature showed the importance of establishing and incorporating the physical environment as a healing space, which has been conceptualized by LaTorre (2006) as being co-constructed between the therapist and client. Research findings from other disciplines, such as nursing and psychiatry, have acknowledged how individual preferences, different levels of sensitivity and distractibility, as well as the levels of intimacy associated with topics of discussion, could impact the ideal healing environment from patients’ perspectives (Gregory et al., 2022; La Torre, 2006; Sakallaris et al., 2015). However, the significance of stakeholders’ collaboration in constructing and configuring a built environment has also been acknowledged (Pineo et al., 2020; Pineo & Moore, 2022; Senaratne et al., 2023). Since the therapist and the client in a therapeutic environment are the primary stakeholders spending time together in the therapy room, the need to understand their perspectives about what constitutes an ideal therapy room becomes tenable. Moreso, Hickson, et al. (2004) have noted that therapy communication begins with perceptions in the therapy room.

With evidence affirming the importance of the built environment on therapeutic process and outcomes, more research that explores the perception and experience of therapists regarding their working environment and the impact thereof on their therapeutic engagement with clients is needed (e.g., Stanley et al., 2016). We opine that while the office environment’s design and layout influences the client’s perception of the therapist’s competence, it also impacts the confidence and satisfaction of the therapist, which could inform therapeutic relationship with clients.

The current study, therefore aimed to explore the subjective experience of what makes an ideal therapy room from the perspective of clients and therapists co-constructing as the primary stakeholders.

METHOD

Design: This study adopted a qualitative descriptive research design and utilised a grounded theory research method. Qualitative descriptive studies draw from naturalistic inquiry, with a commitment to studying a phenomenon in its natural state to explain it from the perspective of the persons being studied (Nassaji, 2015). The grounded theory method was chosen due to its ability to provide description and interpretation, with the aim of generating a conceptual model for what constitutes an ideal therapy room among the therapy room stakeholders (Dey, 1999). This chosen research design was utilized to explore and describe the perceptions and experiences of therapists and clients regarding therapeutic rooms. The semi-structured interview method was utilised to collect data.

Participants: The selection of participants followed the purposive sampling technique to identify and recruit individuals who have experience in or experienced psychological intervention in a therapy room. Eight (8) individuals comprising three therapists (1 male and two females) with 3-15 years of practice and five clients (3 females and two males) with an age range of 19-25 years participated in the study (see Table 1).

The context of work of the therapists includes within the NHS (one therapist) and in private settings (two therapists) while most client participants (N=4) had their therapy from private settings. The participants for this study included Asian (3), Black (2) and White Caucasian (3) volunteered students and staff recruited from a university setting. However, all participants have knowledge and experience of therapy and indicated that they could provide valid views on the subject matter. All clients were students from different departments who responded to the poster adverts requesting participants who had previous experiences of receiving therapy in a therapy room and could express their views about what constitutes an ideal therapy room. The therapists were not students but affiliated staff members of the university community. They have also been therapy clients as part of their therapy training. Due to the small size of the participants, the age range was used to anonymise the participant’s data further (table 1)

Materials and procedure for data collection: Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of Wolverhampton’s Faculty of Education, Health and Wellbeing ethical research committee. Ethical consideration was adhered to during the recruitment of participants to make their participation voluntary. Also, all the study participants were duly informed of the study’s purpose, procedure and the potential to publish the results, and all those who consented to participate signed an informed consent document. The participants’ confidentiality were protected by carrying out the interviews in their preferred private area, and all responses were anonymised before data analysis. Care was taken not to reveal potential identifying details of persons, places, or practices.

Recruitment was initiated through posted adverts informing interested participants to contact the principal investigator. Following an expression of interest, an interview date and venue were arranged collaboratively based on confidentiality and convenience considerations. All those who volunteered to participate met the criteria of being a client or therapist within a designated therapy room.

An audio recorder was used for the recording of the interviews. The duration of interviews ranged from 25 minutes to 1 hour 15 minutes. The researchers were sampled until data saturation was reached. The goal of a sample size ab initio is to achieve saturation. Moreover, this is a limited-scope research study, and, the focus was on exploring rather than determining through in-depth interviews (Saunders et al., 2019).

Data Analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the data collected from each interview was analysed immediately. In line with the grounded theory approach of constant comparison as suggested by Glaser (1998) and Charmaz’s (2008) constructivist viewpoint, each interview was analysed, and the cumulative findings were used to inform the following interview. The interviews progressed till data sufficiency was reached in line with the theoretical sampling procedure (Dey, 1999). As we started the first process of analysis, that is, open coding, an initial line-by-line coding of the interview transcripts was undertaken by the first author in dialogue with the third author while the second and fourth authors audited the analytic process (Charmaz & Thornberg, 2021; Chun Tie et al., 2019). After completing the interviews, the verbatim transcripts were first printed and used for the open coding to ensure that relevant information was not omitted before transferring the data to the NVivo 11 software for further coding and analysis. The process required the reading and rereading of the transcripts to identify relevant parts that contribute to what is conceptualised as the ideal or non-ideal therapy room. The initial coding identified many processes and ideas inductively. A first list of categories (such as confidentiality, privacy, nice view, distance, purposeful room designation, room meaning, brightness, colourfulness, grounding objects, flexibility, and waiting area) that emerged were then roughly classified in NVivo to bring these codes together.

In consultation with the third author, the first author further divided the initial identified codes into subcategories in this next phase of the analysis, thus resulting in the codes’ connection thematically. In this phase, the basic data was transformed into more abstract concepts. The second author drew these concepts into visual images that could help describe the central categories of what matters most as constituting an ideal therapy room from the therapy room stakeholders’ perspectives (the clients and the therapists). This process is referred to as axial or intermediate coding in grounded theory literature (Birks & Mills, 2015).

The last phase, often referred to as the advanced (or selective) coding, emerged from continuous regular meetings and memo writing, which characterized the initial phases of the analyses. The analysis process was anchored by the first author in consultation with the third author, while the second and fourth authors acted as auditors before finalising the findings. At this stage, the emergent core categories were grouped around the core concepts, capturing the spatial environmental and contextual factors representing the participants’ views of an ideal therapy room.

Reflection and engagement with Credibility

To form conclusions and interpretations, the researchers attempted to stay open to any information coming from the participants’ narratives throughout the data collection and analysis. To boost credibility, at the end of every interview, we asked participants if they would like to add further information that was not addressed during the interview. Although we tried to remain open and transparent about the entire study process, the researchers acknowledge the influence of our perspectives and background in this study. For example, two of the researchers are therapists who may have instructed the focus of the study and analysis. We also have one built environment professional whose curiosity centers around how the environment impacts on people and people in turn impact the environment. This may also have the potential to implicitly guide our assumptions. We endeavoured to control these tendencies as much as possible by ensuring that recruitment was done through a neutral ground where volunteers personally made contact and were recruited through advertisement only. We envisage that the idiographic nature of conducting the interviews and engaging in constant comparison, whereby the initial analysis of one interview informs the next, would control the consequences of the potential implicit guiding assumptions of the researchers. Transparency and openness continued to be central to our consciousness throughout the entire process to answer the central question of our study about what constitutes an ideal therapy room for the therapy room users. The ultimate conceptual model was formed by critically exploring the emergent codes and categories at the research team meetings.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

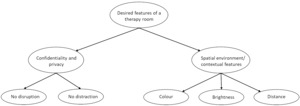

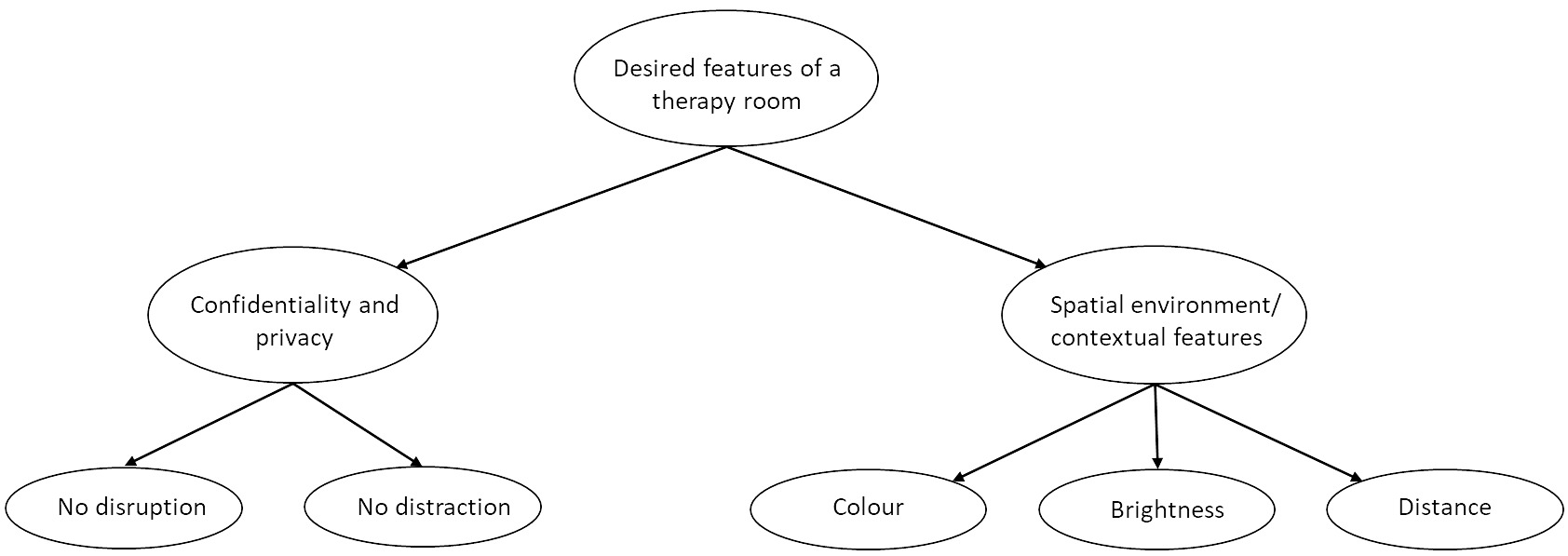

While exploring what makes/constitutes an ideal therapy room, the coding and regrouping the codes revealed the conceptual model of an ideal therapy room with the core categories of confidentiality and privacy and spatial environment/contextual awareness. These main themes emerged from the participant’s responses (see Figure 1)

Confidentiality and privacy

Both therapists and clients described an ideal therapy room as a place that promotes focus on the client with no distraction, i.e., it should be private and confidential so that people outside the room would not be hearing what is being discussed inside the therapy room. The confidentiality theme seemed more recurrent from the therapists than the clients. Not much emphasis was laid on confidentiality by the clients. It might be that the therapists emphasized this aspect as important for an ideal therapy room because this is an integral part of their professional ethical requirement. As noted by one of the therapists: “I would be saying to my clients whatever we say here is confidential but sometimes when me or the client will get a bit louder or err then I would sometimes be conscious that people outside the room might be able to hear” (participant 3 – therapist).

However, the concerns about confidentiality from the client’s perspective is more personified than the therapists’ considering this as a professional requirement. One out of the five client participants mentioned the issue of privacy (twice), whereas the word, confidential was used five times and private was used 5 times by the therapist participants. One client suggested that the therapy room “should be private” and “should not have a window” (participant 6- client). Another client said "I don’t feel comfortable continuing my therapy sessions because I know that the room is not confidential, because I know that people might be hearing our discussions, and I don’t want that" (Participant 7- client)" This client’s response here suggests that if clients perceive a therapy room as not confidential, this could impact the therapeutic relationship and client’s disclosures or even their attendance. Another client also suggested that a therapy room “has to be sound proofed” and "be quiet with no distraction" (Participant 5-client).

Spatial environment/ contextual awareness

This theme seems to be the most recurrent and incorporates several initial codes of comfortability, distance, brightness/colourfulness, nice viewing, room meaning, and focus points. It appears that these all depend on how the spatial environment is arranged within the room to make it an ideal therapy room.

Participants emphasized that a therapy room should be less formal and should not be like an office room (Participants 1 and 2). While one of the client participants expressed a divergent opinion that a therapy room should not have windows as a sign of privacy (Participant 7), all other clients and therapists did not agree with this opinion and instead expressed that a therapy room should have windows. However, the windows should facilitate 'a nice view’ and 'not overlook a brick wall’. This raises a significant challenge in therapy rooms in urban high-rise houses closely built together, with windows overlooking brick walls.

Furthermore, the interviews showed that the participants are particular about efforts being put in place to make therapeutic spaces comfortable for both therapists and clients as they face each other. Also, it was mentioned that an ideal therapy room should have comfortable couches and furniture. The room being adorned with comfortable couches and furniture challenges the settings where the rooms used for therapy are not specially designated for this purpose and are only used because they are available. One participant therapist reiterated, “I’ve worked in lots of different contexts….so one particular challenge that I had in a couple of different jobs around rooms has been when there has been a lack of building space for therapeutic purpose and then ..the only room available has been one that has been used for another nontherapeutic purpose……. So, I was once asked to conduct therapy in an isolation suite essentially a room that had been used for isolation in a secure facility, which I refused to do…. The seat in this room had been used to restrain a client previously and was scratched” (Participant 2- therapist).

However, this therapist refused to use the room to see their client. We wonder whether they would have refused to use this room if they were unaware that it was previously used for restraining clients.

Another participant felt that “Lots of efforts should be put into making a space that is comfortable for both therapist and the client” (participant 4- client)

The need for distance between a therapist and client’s seat “so clients will not feel claustrophobic” (participant 2 – therapist) was expressed. One participant added that there is a need for the therapy room to be "more spacious" and not “make you feel a bit confined (participant 4-client) …when you are baring your soul to somebody and you are confined in a tight space, you feel a bit claustrophobic” (participant 5- client). This consideration suggests that the client’s perception of the therapy room space might impact how “opened” they are to their therapist. It also emphasises the significance of seating logistics within the therapy room and concerns making clients comfortable as an enabler of effective therapy. Issues of lighting and room wall colour emerged prominently in the discussions. Concerns were raised that the light in the room should not be extremely bright, but the room should give enough illumination. All clients in this study preferred therapy in a room painted with bright colours and implied that the perception of colour of the therapy room plays a role in the therapeutic engagement. One of the client participants expressed that “When I see colours and brightness, it just generally makes you feel more, I don’t know… makes me feel more open” (participant 5), and another “colour should be opposite to grey, and like blue. It should be vibrant colours or light colours” (participant 3-therapist).

Our findings align with previous evidence establishing the significant influence of the built environment on therapeutic engagement and process but identified peculiar factors that explain the influence. While Ulrich et al. (2003) argued for the need to make therapy rooms/spaces accommodating and prevent stress, it is unclear what this tangibly means. These authors further pointed out that structural features such as signage and a view of nature contribute to positive psychological and physiological health. Participants in the current study pointed out what an accommodating room looks like and what could stimulate their relaxation in a therapy room. Backhaus (2008) who reported accessories, furniture, colour, sound, and lighting as important components of a therapy room that impact therapeutic engagement and process lends support to the findings from our study.

In literature, the idea of distance between therapist and client during therapeutic sessions has not focused on the physical distance, but on therapeutic distance. Therapeutic distance is “the level of transparency and disclosure in the therapeutic relationship from both client and therapist, together with the immediacy, intimacy, and emotional intensity of a session” (Daly & Mallinckrodt, 2009, p. 559). Egozi, Tishby & Wiseman (2021) identified that client attachment anxiety relates to clients’ and therapists’ experience of each other as “too distant” or “too close” and this affects their therapeutic engagement. The client and the therapist seem to give prominence to proximity and physical distance in this current study.

Focus Point: Another key finding from our study was on the perception of objects in a therapy room, as well as their location and positioning. For instance, pictures on the walls (stone) - grounding/other earthly objects, positioning objects in the corner, and posters around the room with some messages e.g., “time to talk” are beneficial to therapy. Some respondents supported therapy room features as follows:

“nice kind of like stones that were quite a grounding kind of em earthly objects that erm is inoffensive and a bit grounding in some way…so yeah I think there were pictures of stones and maybe a landscape of the sea…” (participant 3 –

“I recently noticed that… there is a little corner that perhaps is more related to my therapist’s kind of beliefs and kind of, sort of.. grounding and ….I guess it’s usually the way they sit it’s kind of opposite to them that little corner, and they have objects in there that perhaps they find calming or maybe grounding for them. I only noticed it recently so I feel it will be nice for a therapy room to have a spot where therapist could look, up looked at and.. they could get grounded too” (participant 3 – therapist)

Pictures on the walls of the therapy room are essential. e.g. Stone may promote grounding, other pictures may promote communication, and disclosure posters around it saying, ‘time to talk.’

The issue of flexibility was raised in the common practice of a shared therapy room. The question of whether there would be a need to tailor the room to suit therapists’ and clients’ desired ideal therapy room was implicated in this comment from a therapist:

"There was a bit of disagreement because somebody new took over the service and they changed the (therapy) rooms, and they put some candles in there and a picture on the wall of some stones. Moreover, it was funny because there was quite a lot of some disagreement within the service about whether they should have done (this)…….. Some of the other counsellors volunteering within that service disagree with them". (Participant 2- therapist)

From the above, there seems to be a lack of understanding from the other colleagues to tolerate the change brought by another colleague to the therapy room. The awareness of the need for flexibility is therefore implicated.

Further exploration also raised the question of whether therapists project their personality to the therapy room they use to see clients as colleagues of this participant were discussing this.

"….. in terms of whether they were kind of injecting some of their personality into that space in a way or that they had an idea about what a therapeutic room should look like (Participant 2- therapist)".

There is an implicit acceptance that the therapy room might be an extension of who the therapist is. This notion supports the rationale for the need to understand the perspectives of the therapists and the clients when considering an ideal therapy room. The codes around comfortability, distance, brightness/colourfulness, nice viewing, room meaning, and focus points fit within the existing theoretical notion of the spatial context for cognitive agents interacting with the spatial environment (Freksa et al., 2005). In line with our findings, a recent study by Sinclair (2020) reported comfortable seating, room temperature, no interruptions, and accessibility of the room as important elements/attributes of a therapy room that aid engagement and outcome of therapy. Similarly, our findings are supported by the exploratory study conducted by Sanders & Lehmann (2019) which reported that the desire for a sense of physical and emotional comfort was a major factor influencing a client’s preference in a therapy room.

Grounding is a concept first developed by Lowen Alexander (1910-2008) who proposed that human beings are physically, emotionally, and energetically grounded to the earth: “We move by the discharge of energy into the ground. (. . .) All energy finds its way into the earth” (Lowen, 2006, p. 71). Most grounding techniques are built upon the assumption that when one is overwhelmed with emotional pain, one needs a way to detach so that one can gain control over one’s feelings and stay safe. This detachment focuses outward on the external world through the sense of sound, touch, smell, and sight rather than inward towards the self (Najavits, 2002).

Conclusion

The findings from this study established identified themes that described the perception and experience of a therapy room by clients and therapists and how these may have influenced therapeutic engagement and process. Findings produced a conceptual model which revealed that confidentiality and privacy were the most important factors that make a room ideal for therapy provision for both clients and therapists interviewed. The spatial arrangement of therapy rooms is also important, especially in making clients feel relaxed and engage with their therapy sessions. While some clients would love a therapy room with a window with a view, others would prefer one without a window for confidentiality and privacy. Furnishing and internal decoration of the therapy rooms were identified as big influencers of clients’ comfort which requires adequate attention. The variety of needs and diverse concepts of an ideal therapy room expressed by the participants in this study demonstrate the difficulty in establishing a space that would perfectly meet the perceived clients’ needs. This study, therefore supports the conceptualised “good-enough therapeutic space” described by Kreshak (2020). Kreshak (2020) follows the idea of the “good enough mother” concept (Winnicott, 1953), which describes how a therapist’s role relates to that of a mother. This concept has been adapted to creating a therapeutic space and other contexts (Ratnapalan & Batty, 2009). The concept supports the creation of a therapeutic room that promotes the holding of “relational space” between the client and therapist. However, while the above are important to consider for an ideal therapy room, the participants in the current study regard confidentiality/privacy and the spatial and contextual features as the core for consideration.

In practical terms, the built environment is important to therapy and its providers; thus, therapists should work cooperatively with relevant stakeholders to provide rooms that will be good enough to meet the expectations of their diverse clients. A prior ‘needs’ or ‘requirements’ analysis should underpin the provision of therapy rooms. A critical factor in this provision is flexibility, which will enable a therapy room to be quickly and easily adapted to the expectations of different clients due to its non-verbal communication ability (Okken et al., 2012; Rapoport, 1982/1990). The ability to rearrange furniture, cover windows and position grounding objects would provide opportunities for such adaptation. This accomplishment will make each client feel more respected and catered for, making them feel more relaxed and engage well with their therapy session/s. However, the collaboration of the therapist colleagues is implicated here if the desired ideal therapy room would be achieved through flexibility. This thus supports the need to involve all stakeholders in the configuration of an ideal therapy room (Pineo et al., 2020; Senaratne et al., 2023) and has implications for psychotherapeutic services to foster such collaboration. The need to balance how the therapy room projects the therapist’s personality to meet the client’s therapeutic needs is also implicated.

Findings from this study will be useful in the field of built environment in terms of constructing with a more defined purpose, as opposed to 'hit and miss, and in the field of psychotherapeutic pedagogy. Further research is suggested to enhance the applicability of these findings to clients and therapists within a broad range of therapeutic settings. Research on the therapeutic room’s perception and extensions to this for defined client groups is also recommended. The recent development in eco therapy has highlighted the need to consider how aspects of the environment may emerge as therapeutic and beneficial to both the client and therapist (Sweetney et al., 2021).

Limitations

The design framework for grounded theory for novice researchers suggested by Chun Tie et al. (2019) has informed the grounded theory concepts and processes adopted in this study as we acknowledge the complexity surrounding grounded theory methodology. We also acknowledge the complexity of reaching a theoretical saturation (Charmaz & Thornberg, 2021), hence the term “data sufficiency” used in this study. We are aware that it may still be possible to modify or change our perspective despite the efforts already put into the data analysis and this study’s procedure. This has implications for further study in this area to challenge our conceptual model.

The researchers acknowledge that the scope of the study was limited to exploring the perceived desires associated with therapy rooms. However, data sufficiency was reached. The recruitment of participants was also limited to a university setting, and the sampling size is small. However, the rigorous use of research techniques ensured the achievement of valid findings.

Future research may consider ethnicity as a criterion for study inclusion to understand how this could have informed responsiveness and views about therapy rooms.