Introduction

In the context of psychotherapy, when the therapist displays empathy towards their client’s difficulties, psychotherapy is more likely to have a positive outcome. The therapist’s empathy towards the client’s problems and emotions strengthens the therapeutic alliance, leading to the desired therapeutic outcome and the accomplishment of therapeutic goals (Nienhuis et al., 2018). Empathy reflects the quality of attachment developed between the therapist and the client (Decety & Cowell, 2014) and acts as a protective factor against the client’s resistance to change (Leahy, 2011). Empathy is one of the fundamental characteristics of the therapist (Rogers, 1995) and a critical skill in all therapeutic approaches (Vaslamatzis et al., 2015).

According to Jeffrey and Downie (2016), there is no specific definition of empathy, but it typically refers to one’s ability to connect with another person’s feelings, thoughts and values (Cuff et al., 2016). In psychotherapy, empathy is influenced by the client’s willingness to share their personal experiences, thoughts and feelings with the therapist (Elliott et al., 2011). Several models have explained empathy, with Davis’s (1980, 1996) model identifying four factors with cognitive and emotional content: perspective taking, fantasy, empathetic concern and personal distress. Perspective taking involves recognizing the other person’s feelings, while fantasy refers to imagining how the other person feels. Empathetic concern involves feeling compassion and warmth towards the other person’s problems and emotions, while personal distress involves negative emotions emerging from contact with other person’s negative emotions. Several factors affect empathy, including the absence of shared values and beliefs between the therapist and the client (Wampold, 2015) and the client’s lack of security within the therapeutic context (Watson & Prosser, 2002).

While empathy reflects the quality of the therapeutic relationship and alliance, clients may perceive empathy as inauthentic when the alliance has difficulties (Elliott et al., 2011). Whether therapists cannot differentiate their own emotions from their client or they experience personal distress, then they may develop burnout and secondary traumatic stress, leading to compassion fatigue (Stamm, 2010). Previous research indicates that counseling psychologists and other mental health professionals experience dysphoria (Charlemagne‐Odle et al., 2014), burnout (Berjot et al., 2017), emotional exhaustion (Miller & Sprang, 2017) and secondary trauma (Ivicic & Motta, 2017; Johnson et al., 2014). Compassion fatigue can occur when one person describes a traumatic event, while the other person attempts to alleviate their pain (Meyers & Cornille, 2013). This condition may explain why compassion fatigue occurs in professions that frequently encounter traumatic events, such as nurses (Nolte et al., 2017) and psychologists (Dehlin & Lundh, 2018).

Compassion fatigue is an emotional state that is often mistaken for an illness or disorder, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, due to indirect exposure to traumatic experiences (Figley, 2013). It is accompanied by cognitive, emotional, physical and behavioral reactions (Stamm, 2010). Professionals experiencing compassion fatigue exhibit emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, reduced achievements (burnout), intrusive thoughts, memories and images, flashbacks, sleep and appetite problems and avoidance of discussing events that are reminiscent of the traumatic event (Stamm, 2010).

Several factors can make therapists more vulnerable to the onset of compassion fatigue, such as their own traumatic experiences (Meyers & Cornille, 2013), lack of social support (Ariapooran, 2014), stress (Lee et al., 2015), low self-efficacy (Bozgeyikli, 2012), and contact with clients who have a history of sexual abuse (Turgoose & Maddox, 2017). Women with less than post-graduate education, working in companies (Arvay & Uhlemann, 1996; Mooney et al., 2017) are more likely to experience compassion fatigue. Psychologists with only a few years of work experience are also more likely to experience compassion fatigue due to lack of experience (Dorociak et al., 2017). Compassion fatigue has serious effects on psychotherapy, as it can cause therapists to distance themselves from their clients’ experience in order to protect themselves (Batson, 2010).

Compassion fatigue is not only the result of the therapist’s close interaction with the client, but also of the fact that therapists do not take care of themselves (Figley, 2013). Despite caring for others, therapists frequently neglect their own personal and professional self-care, leading to compassion fatigue. Therefore, compassion fatigue results from the combination of the therapist’s inability to separate from the client’s emotions and the lack of self-care (Figley, 2013).

There are various factors that can protect professionals from compassion fatigue, such as social support, supervision (Merriman, 2015; Miller & Sprang, 2017), self-care (Adimando, 2018; Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2016), mindfulness (Silver et al., 2018) and self-compassion (Delaney, 2018). Self-compassion is an attitude of care and encouragement that individuals have towards themselves during times of failure and difficulty (Neff, 2003a). It consists of three elements: self-kindness in the face of difficulties and failures rather than self-criticism, recognition of pain as a common experience (common humanity) rather than feeling isolated, and mindfulness of thoughts and feelings in the present moment rather than over-identification with them(Neff, 2003a). Research shows that self-compassion is negatively associated with burnout (Beaumont et al., 2016; Eriksson et al., 2018; Richardson et al., 2020), stress (Eriksson et al., 2018; Finlay‐Jones et al., 2016), anxiety (Finlay‐Jones et al., 2016) and depression (Finlay‐Jones et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2020). Conversely, self-compassion is positively related to compassion for others and empathy. Psychologists who are compassionate towards themselves also tend to show more compassion and empathy towards their clients (Bibeau et al., 2016). Moreover, there is a positive relationship between self-compassion and empathy in nurses (Savieto et al., 2019). However, some research suggests a negative relationship between self-compassion and empathy in male students, while in female students, there is no relationship among the two (Daltry et al., 2018). During the Covid-19 pandemic, the emotional dimension of empathy was negatively related to all dimensions of self-compassion except common humanity. The cognitive dimension of empathy was positively related only to self-kindness and common humanity and negatively to self-judgment (Ruiz‐Fernández et al., 2021). Although the relationship between self-compassion and empathy is positive in psychologists, the literature as a whole shows contrasting results.

A narrative review by Turgoose and Maddox (2017) aimed to identify protective and risk factors for developing compassion fatigue in mental health professionals. Among the protective factors was mindfulness (an element of self-compassion), while among the risk factors was empathy (Turgoose & Maddox, 2017). Empathy can lead therapists to emotional exhaustion (Miller & Sprang, 2017), secondary trauma (Ivicic & Motta, 2017; Johnson et al., 2014), and compassion fatigue (Hansen et al., 2018; Ruiz‐Fernández et al., 2021).

A survey of nurses studied the relationship between empathy (excluding the fantasy dimension) with compassion fatigue and the role of self-compassion in this relationship (Duarte et al., 2016). Self-compassion was negatively associated with personal distress and positively associated with perspective taking, but there was no statistically significant relationship with empathetic concern. When examining each subscale separately, empathetic concern was positively associated with common humanity and the negative dimensions of self-compassion. Personal distress was positively associated with the negative dimensions of self-compassion and negatively associated with the positive ones. Perspective taking was positively correlated only with the positive dimensions. Compassion fatigue was positively correlated only with personal distress and empathetic concern, and there was no correlation with perspective taking. The negative dimensions of self-compassion mediated the relationship between empathetic concern and personal distress with compassion fatigue. Self-kindness and common humanity at low levels have been found to regulate the relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue. Low levels of common humanity also moderated the relationship between personal distress and compassion fatigue (Duarte et al., 2016).

While the relationship between self-compassion and empathy has been studied, there are not enough findings concerning professional psychologists (Bibeau et al., 2016). Moreover, research on the correlation’s direction has shown inconsistent results. Additionally, the role of self-compassion in the relationship between empathy and compassion fatigue has only been studied in one study with nurses (Duarte et al., 2016). As psychologists are professionals with high levels of empathy, it is important to investigate the role of self-compassion in this group as well, as they may be at risk for compassion fatigue.

The aim of this research was to examine the role of self-compassion in the relationship between empathy and compassion fatigue among counseling psychologists. The research hypotheses are:

a) Self-compassion will predict empathy in counseling psychologists.

b) Empathy will predict compassion fatigue in counseling psychologists.

c) The positive dimensions of self-compassion (self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness) will moderate the relationship between empathy and compassion fatigue.

d) The negative dimensions of self-compassion (self-judgment, isolation, over-identification) will mediate the relationship between empathy and compassion fatigue.

Methods

Participants

In the research, 104 counseling psychologists participated, of whom 9.6% were men and 90.4% women. Participants ranged in age from 23 to 53 years old, with a mean age of 35.05 (SD = 4.84). Their work experience ranged from 1 to 29, with a mean of 7.66 and a standard deviation of 4.32. Almost all of the participants had a master’s degree (85.6%) and received training in psychotherapy (87.5%), with Systemic (37.5%) and CBT (35.6%) being the most common types of psychotherapy approaches. Nearly half of the participants worked in private offices (48.1%), while the rest worked in organizations, centers, hospitals, schools and crisis lines. The participants were recruited through social media and various organizations. An invitation was posted, inviting Counseling psychologists to participate in a study. They were informed that all professionals could take part, regardless of their treatment approach or work setting. The sampling method employed was a combination of convenient and snowball sampling.

Materials

The participants completed three online questionnaires and a demographic form. The questionnaires included:

Self-compassion Scale (Karakasidou et al., 2017; Neff, 2003b), which consists of 26 items measuring six subscales based on Neff’s theory (2003a) of self-compassion. The subscales are self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness, self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification. Participants rated their answers on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Almost Never) to 5 (Almost Always). The overall scale and subscales had high Cronbach’s alpha reliability (self-compassion a = .943, self-kindness a = .824, common humanity a = .803, mindfulness a = .765, self-judgment a = .804, isolation a = .734, over-identification a = .773).

Interpersonal Reactivity Index-IRI (Davis, 1980; Tsitsas & Malikiosi-Loizou, in Tsitsas, 2009) was also used, which consists of measuring four dimensions based on Davis’s theory. The dimensions are Perspective taking (e.g. I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision), Fantasy (e.g. I really get involved with the feelings of the characters in a novel), Empathetic concern (e.g. I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me) and Personal distress (e.g. Being in a tense emotional situation scares me). Participants rated their answers on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Does not describe me well) to 4 (Describes me very well). The IRI does not export an overall score that measures empathy, but each dimension is studied separately. The dimensions had high Cronbach’s alpha reliability in the present study (perspective taking a = .806, empathetic concern a = .667, fantasy a= .791, personal distress a = .830).

Professional Quality of Life Scale (Stamm, 2010) was used, which consists of 30 items measuring three subscales: compassion satisfaction (not included in this research), burnout (e.g. I am not as productive at work because I am losing sleep over traumatic experiences of a person I help) and secondary traumatic stress (e.g. I jump or startled by unexpected sounds). Participants rated their answers on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often). The burnout and secondary traumatic stress subscales were grouped together as the compassion fatigue subscale. The back-translation procedure was followed, and the subscales had high Cronbach’s alpha reliability in both the pilot study (compassion fatigue: a = .775, burnout a = .741, secondary traumatic stress a = .728) and the present study (compassion fatigue: a = .886, burnout a = .831, secondary traumatic stress a = .811).

Procedure

Due to Covid-19 restrictions, the research was conducted online using a Google Form. Participants read a briefing form and completed a consent form. The survey lasted for four months, and participants’ responses were kept anonymous. The research was designed in accordance with the ethical guidelines outlined in the British Psychological Society (BPS) code of conduct (2014). Hypotheses were tested using Linear Regression, Moderation and Mediation analyses via SPSS 26.0 version.

Results

The normality of variance was assumed (p>0.05) using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Shapiro-Wilk test. The mean scores of the survey’s variables were in moderate levels (Table 1).

The first and second hypotheses were tested by Linear Regression Model. The first hypothesis examined whether self-compassion and its dimensions (independent variables) predict the dimensions of empathy (dependent variables). Self-compassion explains the 56.1% of the variance in perspective taking, F (1,102) = 132.64, p <.001, b = 5.38, the 35.5% of the variance in empathetic concern, F (1, 102) = 11.71, p <.001, b = 3.56 and the 57.6% of the variance in personal distress F (1,102) = 12.47, p <.001, b = -5.74. Self-compassion and its dimensions did not predict statistically significant the dimension of fantasy (p> .05).

Both the positive and the negative dimensions of self-compassion significantly predict the empathy subscales. Self-kindness explains the 41.8% of the variance in perspective taking, F (1,102) = 74.98, p <.001, b = 3.98. Common humanity explains the 46.2% of the variance in perspective taking, F (1,102) = 89.28, p <.001, b = 3.78. Mindfulness explains the 45.7% of the variance in perspective taking, F (1,102) = 87.78, p <.001, b = 3.97. Self-judgment explains the 33% of the variance in perspective taking, F (1,102) = 51.75, p <.001, b = -3.67. Isolation explains the 36.8% of the variance in perspective taking, F (1,102) = 60.89, p <.001, b = -3.66. Over-identification explains the 31.3% of the variance in perspective taking, F (1,102) = 47.89, p <.001, b = -3.53 (Table 2).

Self-kindness explains the 14.6% of the variance in empathetic concern, F (1,102) = 18.59, p <.001, b = 1.99. Common humanity explains the 26.3% of the variance in empathetic concern, F (1,102) = 37.79, p <.001, b = 2.38. Mindfulness explains the 30% of the variance in empathetic concern, F (1,102) = 45.11, p <.001, b = 2.68. Self-judgment explains the 25.9% of the variance in empathetic concern, F (1,102) = 37.08, p<.001, b = -2.71. Isolation explains the 25.4% of the variance in empathetic concern, F (1,102) = 36.00, p <.001, b = -2.53. Over-identification explains the 27.2% of the variance in empathetic concern, F (1,102) = 39.48, p <.001, b = -2.73 (Table 3).

Self-kindness explains the 36.2% of the variance in personal distress, F (1,102) = 59.48, p<.001, b = -3.91. Common humanity explains the 35.8% of the variance in personal distress, F (1,102) = 58.35, p <.001, b = -3.52. Mindfulness explains the 43.3% of the variance in personal distress, F (1,102) = 79.69, p <.001, b = -4.07. Self-judgment explains the 42.1% of the variance in personal distress, F (1,102) = 75.91, p <.001, b = 4.35. Isolation explains the 67.5% of the variance in personal distress, F (1,102) = 94.12, p <.001, b = 4.37. Over-identification explains the 38% of the variance in personal distress, F (1,102) = 64.22, p <.001, b = 4.09 (Table 4). b=4.37.

The second hypothesis tested whether the dimensions of empathy will predict compassion fatigue. Perspective taking explains the 40.9% of the variance in compassion fatigue, F(1,102)=72.29, p<.001, b=-1.52. concern explains the 16.6% of the variance in compassion fatigue, F(1,102)=21.52, p<.001, b=-1.19. Personal distress explains the 39.2% of the variance in compassion fatigue, F(1,102)=67.44, p<.001, b=1.41 (Table 5). Fantasy subscale did not predict compassion fatigue in a statistically significant way (p>0.05).

A Moderation test was performed to examine the third hypothesis. The dimensions of empathy were the predictor variables, the positive aspects of self-compassion the moderator variables and compassion fatigue the outcome variable. The interaction of perspective taking, fantasy and personal distress with the positive dimensions of self-compassion did not predict compassion fatigue in a statistically significant way (p> 0.05). The interaction between empathetic and self-kindness did not predict compassion fatigue statistically significantly (p> 0.05). Mindfulness and Common humanity moderated only the relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue. The interaction of empathetic concern with mindfulness was statistically significant, b = 0.50, 95% CI [0.06, 0.93], t = 2.25, p = .03. When mindfulness was in lower levels, then there was a statistically significant negative relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue, b = -0.67, 95% CI [-1.31, -0.02], t = -2.04, p = 0.04. When mindfulness was in moderate or higher levels, then no statistically significant relationship was observed between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue (p> 0.05) (Table 6). The interaction of empathetic concern with common humanity was found in a statistically significant degree, b = 0.43, 95% CI [0.03, 0.84], t = 2.11, p = .03. When common humanity was low, then there was a statistically significant negative relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue, b = -0.60, 95% CI [-1.15, -0.04], t = -2.14, p = 0.04. When the levels of common humanity were moderate or high, then there was no relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue (p> .05) (Table 7).

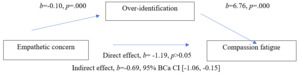

A Mediation test was carried out to examine the last hypothesis. The dimensions of empathy were the predictor variables, the negative dimensions of self-compassion the mediator variables and compassion fatigue was the outcome variable. Negative dimensions of self-compassion did not mediate the relationship between empathetic concern and personal distress with compassion fatigue, as predictor variables statistically predicted compassion fatigue when the negative aspects were both absent and present. As the p index remained statistically significant (p <0.05), it seems that there was a partial rather than a total mediation. The fantasy subscale did not predict compassion fatigue, so it was excluded from Mediation analysis. The negative dimensions of self-compassion mediated the relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue, as when introduced into the model, predictor variable prediction weakened. Specifically, empathetic concern predicted compassion fatigue, b = -1.19, 95% CI [-1.69, -0.68], t = -4.64, p = .000, while when self-judgment entered, prediction weakens, b = -0.40 , 95% Cl [-0.91, 0.12], t = -1.52, p> 0.05 (Figure 1). Empathetic concern predicted compassion fatigue, b = -1.18, 95% CI [-1.69, -0.68], t = -4.64, p = .000, while when isolation entered, prediction weakened, b = -0.45, 95 % CI [-0.97, 0.07], t = -1.71, p> 0.05 (Figure 2). Empathetic concern predicted compassion fatigue b = -1.19, 95% [-1.69, -0.68], t = -4.64, p = .000, while when over-identification entered, prediction weakened, b= -0.50, 95% [ -1.04, 0.05], t = -1.82, p> 0.05 (Figure 3).

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to investigate the role of self-compassion in the relationship between empathy and compassion fatigue among counseling psychologists. The first hypothesis was confirmed, as self-compassion and its positive dimensions were found to predict and positively correlate with perspective taking and empathetic concern, while negatively correlating with personal distress. The opposite results were found for the negative dimensions. These results are consistent with previous research conducted on psychotherapists (Bibeau et al., 2016) and nurses (Savieto et al., 2019), and partially agree with research in health professionals (Ruiz‐Fernández et al., 2021). However, they do not align with research done on students (Daltry et al., 2018), which can be attributed to the characteristics of the sample, as psychologists are a population that learns to cultivate empathy from their bachelor studies in Psychology. The results also have some similarities with a previous study on nurses (Duarte et al., 2016), although the direction of the relationship with empathetic concern differed. This difference can be explained by the fact that psychologists are familiar with negative emotions and come in contact with them in order to reflect them to their clients. On the other hand, although nurses come in contact with their patients’ trauma, they mainly focus on physical rather than psychological and mental pain. Therefore, as self-kindness increases, psychologists, who are well aware of their thoughts and feelings and recognize pain as a common experience, can feel more compassion for others.

The second hypothesis stated that perspective taking, empathetic concern and personal distress predict compassion fatigue. The results confirmed that perspective taking and empathetic concern are negatively associated with compassion fatigue, while personal distress has a positive correlation. These results are consistent with previous studies that have shown that empathy can lead to compassion fatigue (Hansen et al., 2018; Ruiz‐Fernández et al., 2021; Turgoose & Maddox, 2017). Other studies have also demonstrated that empathy can lead to secondary trauma (Ivicic & Motta, 2017; Johnson et al., 2014) and emotional exhaustion (Miller & Sprang, 2017), which are factors contributing to burnout, including the two dimensions of compassion fatigue. However, it appears that empathy leads to compassion fatigue when psychologists are unable to distinguish their own thoughts and emotions from those of their clients, resulting in personal distress.

The third hypothesis was partially confirmed, as the present study found a negative relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue only in counseling psychologists with low levels of mindfulness and common humanity. However, there were no statistically significant results for self-kindness. Also, no statistically significant results emerged when perspective taking and personal distress were the predictor variables. These results match previous research (Duarte et al., 2016). Mindfulness and common humanity play a regulatory role in the relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue, but only at low levels, as seen in previous research (Duarte et al., 2016). When mindfulness levels are low, psychologists may have an imbalanced experience with their thoughts and feelings. This can result in low levels of compassion for others, leading to compassion fatigue as they disconnect from the client’s experience (Batson, 2010; Berjot et al., 2017), causing negative effects in therapy and frustration, leading to compassion fatigue (Dehlin & Lundh, 2018). Similar results are observed when common humanity is low, as individuals who score low on common humanity are less likely to seek help (Ozlem et al., 2017). For example, psychologists with low levels of common humanity may discourage themselves from asking for help such as supervision which works protectively against compassion fatigue (Merriman, 2015; Miller & Sprang, 2017). Self-kindness was not a statistically significant moderator factor, likely due to the sample’s characteristics. It seems that people who feel kindness for themselves can more easily feel kindness for others (Savieto et al., 2019), but psychologists, usually do not care for themselves, even if they take care of others (Figley, 2013). Taking perspective did not show statistical significance as in previous research (Duarte et al., 2016), probably because emotional contact is not necessary in taking perspective (Davis, 1980, 1996). Positive aspects of self-compassion did not regulate the relationship between personal distress and compassion fatigue, likely due to the sample’s moderate levels in the positive dimensions. Higher levels may have shown different results. Self-compassion alone cannot regulate the relationship, but in combination with other factors, such as supervision (Merriman, 2015; Miller & Sprang, 2017) or professional values (LeJeune & Luoma, 2019), it may work protectively against compassion fatigue.

The fourth hypothesis was partially confirmed, as the negative dimensions of self-compassion were found to mediate the relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue. When psychologists fail to show compassion to their clients, it can lead to an increase in self-criticism and difficulties in managing their emotions and thoughts, which can exacerbate compassion fatigue. This intensifies compassion fatigue, as they feel inadequate in their role as therapists. These findings are consistent with previous research (Duarte et al., 2016). However, there was no total mediation when perspective taking and personal distress were the predictor variables. In the current study, there was a partial rather than a total mediation and the results suggest that perspective taking and personal distress still predict compassion fatigue regardless of the negative dimensions of self-compassion. It is possible that other factors not included in the present study may fully mediate this relationship. It should be noted that the third and fourth hypotheses were based on a single study carried out in a different population (nurses) (Duarte et al., 2016) from the present study, so the results should be interpreted with caution.

The fantasy dimension did not show statistical significance, which can be attributed to the content of the items which refer to fictional scenarios (e.g. novel, movie) rather than real client cases. Additionally, the previous study did not include the fantasy dimension, as it was not relevant to their research purpose (Duarte et al., 2016).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The limitation of the study were the overrepresentation of females in the sample as well as participants with a Systemic and CBT background. Another limitation was that the participants were not divided according to specialization, so there is no specific data on whether the specialization has a role on the variables studied. Also, the recruitment method was based on non-probability sampling method, so the results are not representative and generalized. Additionally, the Professional Quality of Life Scale (Stamm, 2010) was not adapted to Greek and was administered through a back-translation process. Future research should aim to re-examine the relationship between self-compassion and empathy, as well as the role of self-compassion in the relationship between empathy and compassion fatigue in psychologists, in order to obtain more precise data for this population. Also, future research can address whether the specialization influences the professionals’ self-compassion, empathy and compassion fatigue.

Implications

Self-compassion and its positive dimensions are positively related to perspective taking and empathetic concern, while being negatively related to personal distress. On the other hand, the positive dimensions of self-compassion yield the same results, while the negative dimensions yield opposite results. In addition, there is also a negative relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue in psychologists with low levels of common humanity and mindfulness. Finally, the negative dimensions of self-compassion mediate the relationship between empathetic concern and compassion fatigue. It would be useful for counseling psychologists to take part in self-compassion interventions since the literature supports that psychologists with limited work experience are more likely to suffer from compassion fatigue (Hopwood et al., 2019).

These findings are significant, as they shed light to how counseling psychologists can protect themselves from compassion fatigue. Self-compassion is a crucial tool that can shield them by allowing them to be kind to themselves, connected to others, and mindful of their thoughts and emotions in the present moment. In their practice, counseling psychologists should participate in self-compassion interventions to strengthen themselves, which will enable them to empathize with their clients, enhance the therapeutic relationship, and positively impact the therapeutic outcome. By shielding themselves from compassion fatigue and its negative consequences to their health and job, they will be better equipped to serve their clients.