Introduction

Character strengths are traits that are positively and morally valued and help individuals reach their potential, develop and flourish (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). They are considered to reflect one’s “good” core characteristics and the key to be the best version of oneself, affecting the way one thinks, behaves, and feels, leading them to do the right thing (Pezirkianidis et al., 2020; Pezirkianidis & Stalikas, 2020). Peterson and Seligman (2004) introduced the Values in Action (VIA) classification of character strengths and, until now, the study of character has been found to be of high importance for psychological interventions. The cultivation and application of character strengths in everyday lives, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, has been found to predict several wellbeing indices, such as life satisfaction, orientations to happiness, and PERMA wellbeing components (Pezirkianidis et al., 2021; Tilkeridou et al., 2021; Vasileiou et al., 2021; Wagner et al., 2020), as well as to build psychological resilience against adversities (Güsewell & Ruch, 2012; Martínez-Martí & Ruch, 2017).

Character Strengths and Positive Friendships

Based on several philosophical traditions and scientific findings, one’s character is strongly associated with positive relationships, and especially with positive friendships. In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle described positive friendships as “those that build character”, while Park and Peterson (2009, p. 1) defined character as “what friends look for in each other”.

Friendship is one of the most significant interpersonal bonds in one’s life (Fehr & Harasymchuk, 2018; Mitskidou et al., 2021). Positive friendships demonstrate high levels of quality, low levels of conflict, and help individuals thrive both psychologically and physically (Demir, 2015; Holt-Lunstad, 2017). Based on the model of Mendelson and Aboud (1999), a friendship’s quality is based on six positive functions, namely: stimulating companionship, help, intimacy, reliable alliance, emotional security, and self-validation. Stimulating companionship involves doing enjoyable things with a friend; emotional security includes comfort and reassurance provision in stressful situations that cause fear, anxiety or anger; reliable alliance refers to knowing that one can count on one’s friend; help is the support, assistance, and guidance provided by a friend; self-validation is the encouragement by a friend to maintain a positive self-image, and, finally; and intimacy refers to self-disclosure (Fehr & Harasymchuk, 2018).

Even though the crucial role of friendship in one’s life has been highlighted over the years, most of the available literature has focused on those who are in emerging adulthood (Demir, 2015). Existing studies have found that friendship quality predicts several wellbeing indices, such as the experiencing of positive emotions (Demir et al., 2017), a well-developed social life (Liebler & Sandefur, 2002), perceived support from significant others (Cyranowski et al., 2013), and accomplishments (Bronkema & Bowman, 2017).

However, research examining the associations of positive friendships with character are scarce. From a broader perspective, recent studies have shown that specific character strengths, foremost kindness, teamwork, and love, but also curiosity, honesty, zest, social intelligence, fairness, leadership, gratitude, hope, and humor, have strong associations with the social facet of wellbeing in adults, (i.e., positive relationships with others; Pezirkianidis et al., 2020; Wagner et al., 2020). Moreover, another study found that when an individual displays the character strengths of love, kindness, social intelligence, and honesty in every-day life, they tend to experience higher levels of loving interactions with others (Gander et al., 2021). Also, specific character strengths including love, teamwork, and leadership have been found to be displayed more frequently in close personal relationships, (i.e., between family and friends Wagner et al., 2021), while close relationships with others increase the likelihood of positive consequences of strengths-related behavior (Lavy et al., 2014).

The aforementioned studies highlight the vital role of character strengths on social wellbeing. Studies examining romantic and marital relationships found that levels of character strengths, and the extent to which character strengths were displayed in the relationship predicted the relationship satisfaction and quality of both members (Boiman-Meshita & Littman-Ovadia, 2022; Lavy et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, a study conducted by Wagner (2019) in adolescents laid the groundwork for mapping the relationship of character strengths with friendship variables. Based on Wagner’s findings, specific character strengths show the strongest positive correlation with positive relationships with classroom mates, (i.e., love, kindness, social intelligence, teamwork, perspective, and humor). Moreover, the same study found that specific character strengths, (i.e., love, kindness, teamwork, and social intelligence), are associated with both friendship quality and satisfaction in dyads of best friends, while additional strengths showed a strong connection to friendship quality, (i.e., perspective, bravery, honesty, leadership, gratitude, and humor). At the microlevel of individual friendship functions, this study found that different character strengths are associated with specific friendship functions.

Previous study findings regarding the relationship of adult friendship and character are lacking. Only one study secondarily examined this relationship, and found that a set of character strengths (curiosity, honesty, zest, love, kindness, social intelligence, teamwork, fairness, leadership, gratitude, hope, and humor) positively correlated with friendship satisfaction, while three character strengths, (kindness, social intelligence, and humor) were additionally correlated with spending more time with friends (Ruch et al., 2010). Since social wellbeing is of high importance for adults, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic that fiercely affected people’s social life (Dahlberg, 2021; Meijer et al., 2022), there is a need to identify personal characteristics, (i.e., character strengths, that are associated with positive relationships with others, and especially positive friendships) .

Individual Differences in Character Strengths and Friendships During Adulthood

Mapping the relationship between character strengths and adult friendship is in its infancy since both variables fluctuate during adulthood. Both age and gender affect them. Regarding the effects of gender on character strengths, a meta-analysis showed that men and women share similar character strengths but there are significant gender differences on their levels (Heintz et al., 2019). In other words, women report higher scores on the strengths of love, kindness, appreciation of beauty, and gratitude, and love of learning, while men report higher scores of creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, perspective, humor, and bravery (Linley et al., 2007; Pezirkianidis et al., 2020; Ruch et al., 2010). In general, women’s ratings on character strengths are higher than men’s (Linley et al., 2007). Concerning the effects of age on character strengths, a positive relationship was found. More specifically, older adults (above 35 years) report higher levels on strengths of restraint, i.e., self-regulation, modesty, prudence, and forgiveness, strengths of justice, (i.e., fairness, teamwork, and leadership), most of the transcendent strengths, (i.e., hope, gratitude, spirituality, and appreciation of beauty), but also on specific intellectual strengths, such as curiosity and love of learning (Linley et al., 2007; Pezirkianidis et al., 2020; Ruch et al., 2010). However, younger adults (below 34 years) report higher levels of the humor strength (Pezirkianidis et al., 2020).

Moreover, there are individual differences on the number of friends and friendship quality. Friends are important for both men and women (Marion et al., 2013), who tend to create and maintain same-sex friendships. In Greece, three quarters of adult friendships are between individuals of the same sex (Christakis & Chalatsis, 2010), but there are significant differences on their functions. Women friendships are mostly characterized by trust, intimacy, emotional security, emotional expression, self-disclosure, and self-validation, while men friendships feature stimulating companionship, practical support, honesty, and authenticity (Bagwell et al., 2005; Christakis & Chalatsis, 2010; Mendelson & Aboud, 1999). In opposite-sex friendships, on the other hand, there are no gender differences among the two members on the levels of intimacy, practical support, and self-disclosure (Christakis & Chalatsis, 2010; Gillespie et al., 2015).

In regard to the effects of age on adult friendship variables, there is a negative correlation between age and the number of friends (Wrzus et al., 2013). Young adults report a mean number of three to four friends, while older adults report a mean of two or three (Christakis & Chalatsis, 2010), since they focus on developing other domains of their lives, such as work, marriage, and children (Neyer et al., 2014). Moreover, there are differences on friendship quality among age groups. Young adults focus on stimulating companionship and social support provided by friends, while older adults satisfy their needs for intimacy mostly by spouses (Wrzus et al., 2013, 2017).

Do Character Strengths-based Interventions Build Positive Relationships?

Since the birth of positive psychology, many character strengths-based interventions have been designed and applied in adults aiming and achieving to promote their mental health and wellbeing (Ruch et al., 2020; Schutte & Malouff, 2019). Some of them focus on identifying and cultivating a number of strengths, such as signature strengths, lesser strengths or strengths that mostly correlate to wellbeing levels, (i.e., curiosity, zest, gratitude, hope, and humor; Proyer et al., 2013, 2015) and other interventions focus on enhancing specific strengths, (e.g., forgiveness, kindness or gratitude; Ruch et al., 2020). Mostly, researchers focus on the effectiveness of the character strengths-based interventions in wellbeing indices, such as happiness, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety, and stress (Ghielen et al., 2018).

Nevertheless, a few studies shed light on the interpersonal effects of character-strengths interventions. These studies mainly focus on the enhancement of interpersonal strengths, such as forgiveness, gratitude, love, and kindness, and found that forgiveness interventions lead to higher levels of relationship effort and satisfaction, and lower levels of negative conflict strategies and interpersonal behaviors in healthy relationships rather than the troubled ones (Aalgaard et al., 2016; Zichnali et al., 2019). Also, gratitude interventions build positive relationships, since they increase trust, connectedness with others, the likelihood one will engage in prosocial behavior, empathy, intimacy, relationship satisfaction, and perceived quality of friendships (Kerr et al., 2015; O’Connell et al., 2018; Parnell et al., 2020). In addition, love and kindness interventions increase the levels of trust, social skills, acceptance of others, positive social interactions, social support, and sense of connectedness (Hutcherson et al., 2008; Kerr et al., 2015; Symeonidou et al., 2019). Taking everything into account, psychological interventions based on interpersonal character strengths have been found to build positive relationships with others.

However, there is a lack of research on the effectiveness of interventions focusing on non-interpersonal character strengths, e.g., curiosity, bravery, and honesty, on relational variables, such as relationship satisfaction and quality, even though these character strengths were found to predict positive relational outcomes (Ruch et al., 2010; Wagner, 2019). Also, there are no research findings on the relationship between character strengths and adult friendships that could benefit the design of interventions focusing on building positive adult friendships.

The Present Study

The present study aims to investigate the relationships between character strengths and adult friendships and the role of individual differences on this relationship. These findings will lay the groundwork for the design of strength-based psychological interventions focusing on building positive adult friendships.

Thus, the present study will focus on answering the following research questions: (1) Do specific character strengths significantly correlate with adult friendship functions, overall friendship quality, friendship satisfaction, and number of friends? (2) Do specific character strengths significantly predict adult friendship quality, satisfaction, and number of friends? (3) Do age, gender, and gender of the dyad of friends moderate the relationship of character strengths with adult friendship quality, satisfaction, and number of friends?

Based on the literature, we hypothesized that: (H1) almost all character strengths (apart from open-mindedness, prudence, self-regulation, hope, and spirituality) will be positively correlated with, and predict positive friendship outcomes (Ruch et al., 2010; Wagner, 2019) and (H2) the relationships between (a) spirituality and friendship satisfaction, and (b) spirituality, kindness and friendship quality will be moderated by gender (Wagner, 2019).

Method

Participants

A total of 3051 Greek adults aged from 18 to 65 years old participated in the study. Over half of the participants (58.5% ) were women and their mean age was 37.39 (SD = 13.11). More specifically, 22.2% of the participants were aged between 18 and 24, 22.9% between 25 and 34, 19.1% between 35 and 44, 21.7% among 45 and 54, and 12.3% of them were between 55 and 65 years old (1.8% missing ages). Regarding their marital status, 44.2% of the participants were unmarried, 43.8% married, 5.6% divorced, and 1.4% widowed (5% missing status). Moreover, 46.3% of them had children and most of them reported to work in the present time (71.1%). Concerning their educational level, most of them were university graduates (40.3%), while 8.8% were university students, 27.8% high school graduates, 6% middle school graduates, and 12.3% held a post-graduate degree.

Regarding their friendships, the participants reported a mean number of three close friends. More specifically, 5.2% of them reported having no close friends, 10.8% one close friend, 25.6% two, 26.5% three, 15% four, 8.9% five and 7.8% more than six close friends. As for the gender of the dyad of friends, 29.8% of the dyads consisted of same-gender men and 43.1% were same-gender women, while 3.8% of men reported on a friendship with a woman and 5.3% of women have chosen a friendship with a man.

Measures

Character Strengths. The Values in Action – 114GR (Pezirkianidis et al., 2020) is the Greek version of VIA-Inventory’s of Strengths short form and contains 114 items that measure 24 character strengths based on Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) classification. The difference between the VIA-114GR and the original VIA-120 is the deletion of six items that did not fit the data collected from the Greek population. Participants use a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 0 = very much like me to 4 = very much unlike me) to report the extent to which each item describes them. In this study, the internal consistency of the 24 subscales ranged from α = .70 (modesty) to α = .85 (persistence).

Positive Friendship Functions and Satisfaction from Friendship. The McGill Friendship Questionnaire – Friendship Functions (MFQ-FF; Mendelson & Aboud, 1999; Greek version: Pezirkianidis, 2020) consists of 30 items that measure the positive functions of a specific friendship, namely: (a) stimulating companionship, (b) help, (c) intimacy, (d) reliable alliance, € emotional security, and (f) self-validation (sample item: “___ helps me when I need it”). The Greek-short version of the McGill Friendship Questionnaire – Respondent’s Affection (MFQ-RA; Mendelson & Aboud, 1999; Greek version: Pezirkianidis, 2020), which consists of five items, was used to measure satisfaction and positive feelings regarding a specific friendship. A sample item is “I am satisfied with my friendship with __”. The original version of the MFQ-RA consists of 16 items, but the content of the items overlaps strongly. In this study, the participants were asked to bring in mind one of their closest friends. The answer scales in both measures ranged from 0 = never to 8 = always. Regarding the psychometric properties of the two measures, the six-factor structure of the MFQ-FF yielded an acceptable fit to the data: χ2/df = 7.33, GFI = .90, CFI = .92, NFI = .91, IFI = .92, TLI = .91, SRMR = .04. Also, the internal consistencies of the six friendship functions’ subscales ranged from α = .86 (help) to α = .91 (stimulating companionship). Moreover, the single-factor model of the MFQ-RA yielded adequate internal consistency (α = .94) and an acceptable fit to the data: χ2/df = 21.54, GFI = .96, CFI = .97, NFI = .97, IFI = .97, TLI = .96, SRMR = .05.

Demographics. Participants provided demographic information concerning gender, age, marital status, educational level, employment status, and number of close friends (a definition of close friendship was provided).

Procedure

Research data was acquired from students of the Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences during the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 academic years. The students were trained to recruit adults of their social milieu without providing them any external incentives or compensation. The participants took part in the study following a brief about study aims and anonymity of their responses and they provided informed consent. The data were recorded on answer sheets, scanned using the Remark Office OMR (Gaikwad, 2015), and were analyzed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences 21 (Hinton et al., 2014) and IBM SPSS PROCESS command (Hayes & Matthes, 2009).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analysis

First, we tested if the data for each variable significantly deviate from a normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test and the results showed that all variables did not follow a normal distribution. Thus, non-parametric analyses were used (correlation analysis using Spearman’s Rho coefficient and exploration of independent samples’ differences with Mann Whitney U tests).

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for the character strengths and the friendship variables, (i.e., the six friendship functions, overall friendship quality, friendship satisfaction, and number of friends), as well as correlations with age and gender differences. The results concerning the VIA-114GR indicate that female participants report higher scores on most character strengths - most notably love, kindness, and love of learning, while men report slightly higher scores of specific strengths, namely creativity, bravery, and humor. Also, older participants reported higher levels of most character strengths, while younger ones reported higher levels only for humor. Additionally, female and younger participants reported higher levels of positive friendship functions, overall quality, satisfaction, and number of friends.

Correlation Analysis

Second, to test the first research question, we tested for significant relationships among character strengths and friendship variables, while controlling for influences of age and gender (see Table 2). The results of the partial correlation analysis showed positive statistically significant correlations amongst almost all character strengths and friendship variables. Most notably, friendship functions, satisfaction, and overall friendship quality mainly correlated with the strengths of love, kindness, and honesty; r(3051) ranged between .24 and .42, while the number of friends showed low correlations with a few strengths and especially with curiosity r(3051) = .15, p < .001; humor, r(3051) = .13, p < .001; and kindness, r(3051) = .12, p < .001.

Multiple Regression Analysis

To test the second research question, we conducted multiple regression analyses to examine if character strengths can explain a part of friendship quality, satisfaction or number of friends’ variance (see Table 3). Before the analysis, assumptions testing was done, and all assumptions were met. The results showed that 23 percent of a friendship’s quality can be significantly predicted by higher levels on the character strengths of love, β = .26, p < .001; kindness, β = .20, p < .001; honesty, β = .07, p = .007; and curiosity, β = .05, p = .038. In addition, 31 percent of the satisfaction by a friendship can be predicted by higher levels on the strengths of kindness, β = .32, p < .001; honesty, β = .25, p < .001; love, β = .12, p = .006, and bravery, β = .09, p = .023, and lower levels of modesty, β = -.16, p < .001, and spirituality, β = -.17, p < .001. Lastly, a small percent of number of friends’ variance (R2 = .04) can be explained by higher levels of curiosity, β = .20, p < .001, and lower levels of persistence, β = -.13, p < .001.

Moderation Analysis

To investigate the third research question, a moderation analysis was performed. The outcome variables were friendship quality, friendship satisfaction, and number of friends. The predictor variables were the character strengths found to predict each outcome variable based on the multiple regression analysis results. The moderator variables were age, gender, and gender of the dyad of friends, (i.e., same-sex among men, opposite-sex, and same-sex among women friendship).

The interactions between the character strengths of curiosity, honesty, kindness, and love and the moderating variables of age, gender, and gender of the dyad were found to be statistically non-significant in the prediction of friendship quality. However, the interaction between bravery and gender was found to be statistically significant regarding the prediction of friendship satisfaction [B = 32.82, 95% C.I. (32.47, 33.18), p < .001]. Regarding both men [B = .62, 95% CI (.38, .86), t = 5.124, p < .001] and women [B = .29, 95% CI (.13, .44), t = 3.670, p < .001], the conditional effects were statistically significant, but the strongest relationship between friendship satisfaction and bravery was found among men (see Figure 1).

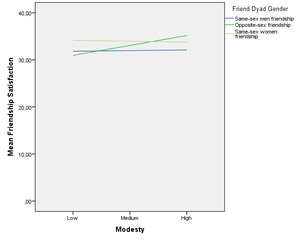

Moreover, the interaction between the character strength of modesty and age was found to be statistically significant for the prediction of friendship satisfaction [B = 32.99, 95% C.I. (32.64, 33.35), p < .001]. The conditional effects were statistically significant only at high moderation (see Figure 2), i.e., a relationship between friendship satisfaction and modesty was found only among older participants [B = .24, 95% CI (.07, .41), t = 2.702, p = .007]. In addition, an interaction between modesty and the gender of the dyad of friends was also found concerning the prediction of friendship satisfaction [B = 31.92, 95% C.I. (31.31, 33.60), p < .001]. The conditional effects were statistically significant only at opposite-sex friendships (see Figure 3); a relationship between friendship satisfaction and modesty was found only at opposite-sex friendships [B = .07, 95% CI (.28, 1.12), t = 3.274, p < .001].

Finally, an interaction between persistence and gender was found concerning the prediction of number of friends [B = 3.11, 95% C.I. (3.00, 3.17), p < .001]. The conditional effects were statistically significant only among men (see Figure 4). The strongest relationship between the number of friends and persistence was found among men [B = -.05, 95% CI (-.08, -.02), t = -3.044, p = .002].

Overall, the results indicate that higher levels of modesty among older adults and in opposite-sex friendships predict higher levels of satisfaction from friendship as well as higher levels of bravery among men. Also, higher levels of persistence among men predict less friends in adulthood.

Discussion

The present study focused on investigating the relationships between character strengths and adult friendships and the role of individual characteristics, (i.e., age and gender), on this relationship. This study is the first aiming to investigate this relationship in order to lay the groundwork for the design of strength-based psychological interventions focusing on building positive adult friendships. The main findings highlight the positive correlation between most character strengths and positive friendship outcomes. More specifically, research results indicate that character strengths of love, kindness, honesty, and curiosity predict adult friendship quality, while curiosity and persistence predict the number of friends, and kindness, honesty, modesty, spirituality, love, and bravery predict satisfaction from adult friendship. Most of these relationships were not moderated by age or gender.

These findings partially agree with the actor effects of character strengths on friendship quality and satisfaction based on previous studies. Wagner (2019) found no effects of spirituality and positive effects of modesty on friendship satisfaction in adolescents, while our findings support a negative effect of both strengths. Also, Wagner (2019) found significant actor effects on friendship satisfaction and quality by almost all character strengths (except for hope, open-mindedness, forgiveness, prudence, self-regulation, and spirituality) in accordance with Ruch and colleagues’ findings in adults (2010). Moreover, Wagner (2019) found gender to have a moderation effect on the relationships between spirituality, kindness and friendship outcomes that were not confirmed by our study in a sample of adults. Conversely, the findings of the present study indicate that higher levels of modesty among older adults and in opposite-sex friendships predict higher levels of satisfaction from friendship as well as higher levels of bravery among men. Also, higher levels of persistence among men predict less friends in adulthood. These findings are very important for designing individualized character strengths interventions, but further studies should be conducted to confirm them.

It is worth mentioning to better understand the aforementioned findings that the results of the present study concerning the associations of character strengths (Martínez-Martí & Ruch, 2014; Pezirkianidis et al., 2020; Wagner, 2019) and friendship variables (Bagwell et al., 2005; Pezirkianidis, 2020; Wrzus et al., 2013, 2017) with gender and age were similar to previous findings in the same cultural context, other cultures, and younger participants. More specifically, the findings agree that female and older participants report higher scores on most character strengths, while men report higher scores of specific strengths including bravery and a few strengths do not correlate with age, such as love and curiosity. In addition, it was confirmed that female and younger participants report higher levels of friendship quality, satisfaction, and number of friends. Below we discuss the effects of the character strengths found to be important to friendship outcomes on building positive social relationships.

Kindness refers to prosocial actions intended to benefit others (Curry et al., 2018). Acts of kindness help form new relationships through reducing social interaction anxiety (Shillington et al., 2021) and strengthen the existing social bonds over time through increasing their quality and the satisfaction derived from them (Chancellor et al., 2018; Wieners et al., 2021). We could assume that acts of kindness in the context of friendship are connected with higher levels of emotional and instrumental support, which are key components of friendship quality (Mendelson & Aboud, 1999). These acts of kindness increase gratitude feelings and reciprocity in the relationship and lead to more satisfaction with friendship (Algoe et al., 2008; Alkozei et al., 2018). Kindness combined with love characterizes individuals that value their close relationships (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) and is described as the ability to accept all parts of them, including positive and negative parts, as an unconditional love without desire for people to be a certain way (Salzberg, 1995). This predisposition relates to higher levels of acts of kindness, being compassionate toward others and cultivate an attitude of unconditional love (Boellinghaus et al., 2014), while neuroimaging studies suggest that it enhances activation of brain areas that are involved in emotional processing and empathy (Hofmann et al., 2011). Acceptance is a key concept in adult friendship and is achieved through self-validation, i.e., a sense that the friend provides reassurance and encouragement resulting to maintaining a positive self-image (Fehr & Harasymchuk, 2018), social comparison with friends and similarity with them and leads to higher levels of positive experiences and satisfaction in friendships (Wrzus et al., 2017).

Honesty refers to the tension of being authentic and tell the truth to self and others (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Honesty predicts less frequent negative exchanges with others (e.g., criticism, perceived anger, and perceived neglect), greater levels of relationship satisfaction (Tov et al., 2016), and choosing honest friends (Ilmarinen et al., 2016). Thus, this characteristic is closely related to positive experiences in relationships. However, telling the truth often entails delivering negative information. This is associated with short-term social harms, (e.g., shame or anger), but also to long-term relational benefits, such as greater levels of trust and intimacy (Levine et al., 2020). Honesty has been mostly studied in romantic relationships, in which is idealized. Thus, romantic partners agree on specific rules regarding honesty and dishonesty. Complying with these rules predicts relationship resilience, satisfaction, and conflict (Muñoz & De Los Reyes, 2021; Roggensack & Sillars, 2014). These mechanisms could also explain the findings of the present study regarding the positive relationship between honesty and positive friendship outcomes.

Curiosity is described as a strong desire to know or learn something. Several researchers focused on its relational facet talking about social curiosity, (i.e., wondering and desiring to find out about others and being curious about those who are different; Phillips, 2016). Social curiosity differs by gossip, since it is more driven by a desire to gather information about how other people feel, think, and behave and the need of belonging amongst them (Hartung & Renner, 2013). Thus, social curiosity relates to forming and maintaining social relationships, since socially curious people take advantage of any opportunities for closeness and have the skills to create stimulating experiences with other people, like interesting conversations, that strengthen their relationships and predict less relational boredom (Hebert, 2022; Kashdan et al., 2011). It is therefore reasonable to conclude and support the finding of the present study that curious people tend to have more friends and achieve higher levels of friendship quality that is based to greater stimulating companionship and intimacy (Mendelson & Aboud, 1999).

Modesty refers to the ability to acknowledge personal characteristics, abilities, and limitations but also being humble (Tangney, 2000). Modesty has been found to positively predict the quality and satisfaction in social relationships (Peters et al., 2011; Tov et al., 2016) and especially in romantic relationships, where it also predicts forgiveness and revenge levels (Farrell et al., 2015; Van Tongeren et al., 2014). These findings are based on the finding that modest and humble individuals cope better with interpersonal tension and conflict (Webster et al., 2018). However, in the present study, modesty was found to negatively affect relationship satisfaction except for older adults and in opposite-sex friendships. More studies should be conducted to shed light in the relationship between modesty and positive relational outcomes, especially in adult friendship, while conceptual issues should be raised to better understand this characteristic and if researchers define and measure it in the same way.

Bravery is mostly studied through the concept of trait courage, which refers to the predisposition of engaging in intentional, mindfully deliberated acts that involve an objective risk to the actor and aim to result in a noble good or worthy end (Rate et al., 2007). Courage in social relationships lead to higher relationship quality (Fowers, 2000), while in the present study was associated with greater friendship satisfaction. Since “brave” individuals focus on positive outcomes through risky behaviors, this could be connected to more stimulating companionship and fun in friendship bonds (Mendelson & Aboud, 1999), and especially among men, who engage in more risky behaviors (Byrnes et al., 1999). However, the way individuals demonstrate social courage differs, since feminine individuals become social courageous through being affectionate and sensitive to other’s needs, while masculine individuals are courageous in their social bonds through being more dominant, impulsive, and risk-taking (Howard & Fox, 2020). This could be a further explanation of the present study finding regarding the gender effects on the relationship between bravery and friendship satisfaction.

Spirituality as a character strength describes individuals that concern about an ultimate purpose in life and a higher calling toward love and compassion (Hill & Edwards, 2013). Spirituality is often confused with religiousness, which describes individuals that hold a belief system focused on a divine power and engage in practices to worship that power (Hill & Edwards, 2013). A study focusing on the effects of spirituality and religiousness on positive relationship outcomes found that they predict a warm but somewhat dominant interpersonal style. Also, spirituality was found to predict interpersonal goals that emphasize positive relationships with others and positive relational outcomes, such as greater social support and less conflicts, loneliness, and negative social exchanges. However, specific aspects of religiousness, namely extrinsic religiosity and believing in a punishing God, were found to be associated with a hostile-dominant and a hostile-submissive interpersonal style, which connects to less positive social bonds (Jordan et al., 2014). It is possible that this finding explains the negative effects of spirituality on friendship satisfaction based on the present study results, since spiritual-religious adults could sometimes adopt hostile interpersonal styles.

Persistence refers to the “voluntary continuation of a goal-directed action in spite of obstacles, difficulties, or discouragement” (Peterson & Seligman, 2004, pp. 229–230) and is rarely studied in terms of relationships with others. Researchers have mainly focused on the effects of the frequency and intensity of persistence on romantic relationship reconciliation. In this context, persistence can be translated into mild or extreme reconciliation attempts, (e.g., from repeated calls and visits to threats an abuse; Cupach et al., 2011). Thus, the persistence could be successful to reconciliation but more often is experienced as intrusive and aggravating. Higher levels of relationship rumination and negative feelings about the breakup increase the levels of the persistence (Cupach et al., 2011). Similar mechanisms and reconciliating behaviors are reported between friends (Hojjat et al., 2017). Thus, high levels of persistence that involve extreme reconciliation attempts could lead to less friends in adulthood, in accordance with the findings of the present study.

All in all, the present study sheds light on literature gaps concerning the association between character strengths and adult friendship outcomes. The fact that specific character strengths predict more positive relationships with friends during adulthood has several implications for theoreticians, practitioners, and future studies. This study is the first step to map the associations between character strengths and friendship outcomes in adults in general and more specifically in Greece, where studies and interventions in counselling contexts more and more focus on building positive relationships and, consequently, psychological wellbeing and resilience.

Implications for Psychological Interventions

The findings of the present study add significantly to the understanding of the importance of social relationships by utilizing knowledge of positive psychology and are considered fruitful for the promotion of research on building positive relationships, and specifically friendships in Greece and worldwide. The research findings provide information on which strengths of character predict greater levels of friendship quality and satisfaction during adulthood. These findings are therefore important not only for theory but also for psychological interventions. Counsellors, coaches, social workers, psychologists, and educators in school, work or clinical settings could use the findings of the present study to design character strengths-based interventions in order to build positive friendship relationships. Positive relationships interventions that include strengths cultivation till now focused mainly on interpersonal character strengths. However, the results of the present study highlight the additional positive effects of honesty, curiosity, and bravery on positive friendship outcomes. As a result, counseling psychologists could utilize this knowledge, design, and implement strength-based multi-component interventions to build positive adult friendship relationships in different settings.

For instance, teacher burn out is a huge problem in school settings. However, the protective effect of positive relationships with colleagues on burn out levels has been underlined by numerous studies (e.g., Van Droogenbroeck et al., 2014). Thus, this is fertile ground for school or counseling psychologists to implement strength-based interventions. Similar interventions could be applied in other work settings, where enhancing positive relationships and new friendships among employees could lead to higher job engagement, satisfaction, and performance levels (e.g., Nasurdin et al., 2018; Orgambídez-Ramos & de Almeida, 2017). Moreover, university counseling centers could implement such interventions aiming at reinforcing the fragile psychological health of university students, especially during the post-COVID era (Konstantopoulou et al., 2020), and support their social wellbeing that suffers due to experiences of loneliness (Diehl et al., 2018). Additionally, during individual counselling sessions, psychologists could use the information provided by the results of the present study to strengthen the supportive environment of the client and, in turn, psychological resilience, meaning in life, and experiencing of positive emotions (Feeney & Collins, 2015; Hicks & King, 2009). In general, the attempts to build positive friendships and positive, supportive connections could build better and happier citizens, and, thus, happier societies (Seligman, 2011).

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The present study is based only on self-report measures and a convenience sample, while examines the association of character strengths with positive friendship outcomes from emerging to late adulthood without taking into account several demographic information (apart from age and gender), such as marital status, educational level or parenthood. These limitations might have affected the generalizability of the results and their interpretation, since previous research has highlighted the crucial role of life status and changes in friendship relationships (Fehr & Harasymchuk, 2018). Moreover, the present study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected close relationships in several ways, such as by increasing loneliness, social distancing, frequency of spending time together and paranoid readiness (Meijer et al., 2022) and could have altered the processes that take place in friendships.

Future studies should address the limitations of the present study and focus on further positive friendship variables, such as capitalization of positive events, relational savoring, perceived mattering, and attachment style. Furthermore, future studies should examine both actor and partner effects of character strengths between adult friends on friendship variables and explore the moderating effects of third variables, (e.g., friend types and friendship duration). Moreover, not only the character strengths’ levels but also the extent to which each friend displays specific character strengths during the time spent together should be examined. It would also be interesting to study the role that friendships play in the co-development of character strengths. Moreover, to better understand the relationships between adult friendships and wellbeing it is important to investigate the issue through qualitative or mixed-methods research studies that deepen the experience of friends. In addition, similar research should be contacted after the pandemic to provide important information on whether and how the mechanisms and strengths that relate to positive friendship outcomes in adults have been chenged. Finally, piloting brand-new strength-based multi-component interventions that focus on building positive friendships across adulthood should be a main aim of future studies.