The Predictive and Mediating Role of Self-Compassion in Substance Use Disorders

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have focused on investigating the potential benefits of self-compassion in addiction treatment and recovery research. Scholars increasingly emphasize that focusing solely on reducing substance use symptoms is insufficient. Consequently, researchers in the field of addiction are encouraged to also explore experiences that foster the development of positive emotions as a means of complementing and enriching the inherently demanding recovery process (Hoeppner et al., 2019; Krentzman, 2013).

As addiction progresses, it is common for individuals to experience deterioration in their relationships with themselves and with those around them. This decline often leads to feelings of shame and guilt, which shape the lens through which individuals perceive themselves and the world they inhabit (Scherer et al., 2011). As individuals with addiction encounter significant psychological and emotional challenges during rehabilitation, implementing effective strategies to address these complexities becomes essential for sustainable recovery.

Coping mechanisms appear to be consistent across individuals with substance use disorders, regardless of the specific substance used. Research conducted by Giannouli and Ivanova (2018a) found no significant differences in self-reported coping strategies among individuals addicted to cocaine, cannabis, and methamphetamine, suggesting a common pattern of coping in addiction. In a separate study on individuals with cannabis addiction in Bulgaria, Giannouli and Ivanova (2018b) found that demographic factors such as age, gender, and education did not significantly predict coping strategies. These findings suggest that the coping mechanisms in addiction extend beyond individual characteristics.

Findings from Greece further support the idea that individuals with substance use disorders rely on similar coping mechanisms, regardless of cultural differences. For instance, a large-scale empirical study by Dritsas and Theodoratou (2017) examined substance use prevention in Greece and emphasized the role of both adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies in the onset and maintenance of substance use disorders. These findings underscore the importance of targeting emotional regulation and resilience-building interventions, as individuals with poor coping mechanisms often exhibit a heightened risk of relapse. Similarly, Antoniou and Karteris (2017) examined the dichotomy between active and avoidance-oriented coping strategies in a Greek sample, demonstrating that avoidance strategies perpetuate emotional distress and hinder recovery efforts. Collectively, these studies highlight the necessity of developing psychological interventions that directly address emotion regulation difficulties and maladaptive coping mechanisms.

In this context, self-compassion has emerged as a transformative psychological construct capable of addressing these gaps. By fostering self-kindness, mindfulness, and emotional resilience, self-compassion provides a framework for re-establishing healthier relationships with oneself and others during recovery (Phelps et al., 2018). Unlike traditional coping strategies that focus solely on symptom management, self-compassion addresses the emotional roots of distress and avoidance behaviors, thereby offering pathways for sustainable recovery. Ultimately, self-compassion is not merely a tool for emotional regulation; rather, it represents a comprehensive framework for cultivating a healthier relationship with oneself during times of distress.

Self-Compassion

Conceptualized by Neff (2003), self-compassion comprises three interrelated positive dimensions along with their respective negative counterparts. These dimensions include self-kindness as opposed to self-judgment, the recognition that pain and frustration are intrinsic aspects of human experience (common humanity) as opposed to feelings of isolation, and mindfulness as opposed to over-identification (K. D. Neff, 2012).

A growing body of research has demonstrated that self-compassion is associated with several beneficial outcomes including improved mental health, reduced psychopathological symptoms, and increased motivation for self-improvement. Furthermore, studies have shown a positive correlation between self-compassion and key constructs in positive psychology, including hope, optimism, and psychological resilience (Bluth & Neff, 2018). The absence of the aforementioned psychological resources in individuals’ lives appears to increase the risk of developing substance use disorders and may impede the already demanding detoxification process (Carlyle et al., 2019).

Understanding the mechanisms behind these associations is essential for identifying how self-compassion contributes to psychological well-being. These benefits stem from the mechanisms through which self-compassion addresses the emotional and psychological challenges that individuals face. For instance, self-kindness replaces harsh self-criticism with supportive inner dialogue, thus fostering psychological resilience. Similarly, the recognition of common humanity reframes personal struggles as part of the shared human experience, thereby reducing the isolation that perpetuates shame and guilt. Finally, mindfulness encourages individuals to acknowledge their emotions without judgment or overidentification, mitigating the risks of emotional avoidance and suppression—both of which are strongly associated with relapse and psychological distress (Heinz et al., 2019; Wegner & Zanakos, 1994).

Through a structured, evidence-based approach to emotional regulation, self-compassion offers individuals a sustainable and adaptive coping framework, uniquely suited to the demands of addiction recovery. This framework equips individuals with tools to replace maladaptive coping mechanisms with healthier strategies, addressing the emotional dysregulation that often complicates addiction recovery. Moreover, by fostering resilience and psychological stability, a compassionate stance toward oneself enhances emotional processing and supports sustained recovery outcomes.

Emotion Regulation

According to Ekman (2003), emotions serve as vital guides, providing essential information about situations and directing behavior in ways that enable individuals to manage them most effectively. Emotions range from pleasant to unpleasant, brief to enduring, and vary in intensity from mild to overwhelming. However, the way emotions function varies among individuals, as certain emotions—such as anger, sadness, guilt, or fear—can become overwhelming and intolerable for some individuals (Gillespie & Beech, 2016). Difficulties in regulating emotional experiences often amplify their intensity, contributing to the development of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders (Chen, 2019; K. D. Neff, 2003). In line with broader research on emotion regulation and addiction, studies conducted in Greece provide additional support for emotion regulation’s role in recovery within the Greek population. Dritsas and Theodoratou (2017) found that individuals who lack effective emotional regulation strategies are more prone to maladaptive coping mechanisms, which, in turn, exacerbate the severity of substance use disorders. Additionally, Antoniou and Karteris (2017) highlighted that promoting engagement-based strategies over avoidance-based approaches significantly improves psychological outcomes. These findings provide cross-cultural validation of emotion regulation as a key target in recovery, while also underscoring the relevance of interventions such as self-compassion, which address these deficits at both cognitive and emotional levels.

Thought Suppression

Thought suppression refers to an individual’s conscious effort to ignore or avoid certain unwanted thoughts, which can result in unpleasant emotional states (Efrati et al., 2021; Wegner & Zanakos, 1994). Despite attempts to suppress these thoughts, studies have revealed a paradoxical effect in which unwanted thoughts resurface with greater intensity, monopolizing the individual’s attention. Research indicates that thought suppression inhibits individuals from achieving a coherent sense of self as it obstructs the processing of a full range of emotions (Wegner & Zanakos, 1994). Zinberg’s (1975) conceptualization of addiction through the lens of Ego psychology provides a valuable framework for understanding the mechanisms underlying thought suppression. Specifically, Zinberg (1975) emphasizes the relationship between the Ego and the external environment, positing that addiction represents a state in which the Ego withdraws in an effort to protect itself. As a result, the Ego becomes trapped between the unconscious desires, thoughts, and emotions that the individual attempts to suppress, preventing their expression in the external world. This fragmentation results in the Ego being disconnected from both repressed emotions and thoughts, as well as from the external environment, which is perceived as inhospitable to their expression. Consequently, the individual is unable to construct a coherent sense of self—one that effectively integrates the complexity of internal emotional experiences with the external world and objective reality.

Drawing from this framework, the Self-Regulatory Executive Function (S-REF) Model provides theoretical insights that may also help elucidate the role of thought suppression in emotional dysregulation. The model posits that maladaptive metacognitive processes, such as suppression, exacerbate negative emotional states and reduce cognitive flexibility, making individuals more vulnerable to cravings and relapse (Etsitty, 2022; Mansueto et al., 2022).

Building on this perspective, the Cognitive Attentional Syndrome (CAS) further illustrates how thought suppression functions as a maladaptive strategy that perpetuates emotional distress by intensifying the very thoughts the person seeks to avoid (Etsitty, 2022). This process creates a self-reinforcing cycle that impairs emotional processing, leading to increased psychological distress and potentially driving susceptible individuals toward substance use as an escape mechanism from the intensified emotional burden.

Given the importance of emotion regulation and adaptive coping strategies in addiction recovery, it is essential to explore interventions that effectively target these areas. Substance use disorders pose a significant public health challenge, with relapse rates remaining high despite existing interventions. Research suggests that self-compassion uniquely addresses the psychological underpinnings of substance use disorders by promoting adaptive coping and resilience. However, despite its potential therapeutic benefits, self-compassion has not yet been systematically examined within addiction recovery research in Greece, highlighting an important gap in the literature.

Research Background

Since the 1980s, researchers have sought to understand addiction through the lens of psychological distress. Studies have focused on factors such as vulnerability, dependence, attachment bonds, self-soothing capacity, and emotional dysregulation. It has been widely suggested that individuals often use substances as a form of self-medication, primarily due to difficulties in self-care and a tendency to avoid or suppress unwanted emotions (Fetting, 2011; Khantzian, 1997).

Research by Neff (2003) and Parrish et al. (2018) highlights self-compassion as an effective emotion-focused regulation strategy. Self-compassion fosters emotional awareness, allowing individuals to approach their feelings with understanding, rather than avoidance, underscoring its role in emotion regulation (Held et al., 2018; K. D. Neff, 2012). Numerous studies emphasize the critical role of emotional dysregulation in substance use. Central to this dysregulation is avoidance behavior, for instance, Messman-Moore and Ward (2014) found that difficulties in regulating emotions significantly predicted problematic alcohol consumption among women. Similarly, Kober (2014) and Stellern et al. (2023) demonstrated that individuals often turn to substances as a means of escaping painful emotions. Weiss et al. (2022) further supported these findings, showing that deficits in emotion regulation impair the ability to inhibit maladaptive behaviors, thereby facilitating substance use.

Managing unpleasant emotions can be mentally taxing, often leading individuals to seek immediate relief through substances. Studies consistently demonstrate that individuals with substance use disorders experience greater emotion regulation deficits than non-clinical populations (Fox et al., 2008; Tice et al., 2001). Notably, Veilleux et al. (2014) found that emotional clarity and access to regulation strategies mediate the relationship between negative emotions and substance use, suggesting that emotional dysregulation contributes to substance use by impairing effective coping mechanisms. Stellern et al. (2023), in a recent meta-analysis, examined the extent to which adults with substance use disorders differ from the non-clinical population in their emotional regulation capacities. The findings revealed that individuals with substance use disorders experience pronounced difficulties in accepting their emotions, display impairments in maintaining goal-directed behaviors, exhibit diminished impulse control, and demonstrate significant challenges in identifying and modulating emotional responses. These results suggest that enhancing specific skills, such as distress tolerance, may be a critical component of effective detoxification interventions.

Studies by Chen (2019) and Suh et al. (2008) have also examined emotional regulation deficits in individuals with substance use disorders, emphasizing the role of self-compassion in regulating emotions. Chen’s (2019) study revealed that participants who were struggling with feelings of guilt and shame often resorted to avoidance and emotional suppression through substance use. Conversely, individuals with higher self-compassion levels demonstrated more adaptive responses in various situations. Similarly, Leary et al. (2007) found that participants with higher self-compassion levels exhibited healthier responses to negative life events. Moreover, self-compassion has been shown to predict more effective emotion regulation strategies among adolescents and young adults with substance use disorders (Vettese et al., 2011). Given the crucial role of emotion regulation in behavioral outcomes, difficulties in this area increase the likelihood of engaging in health-risk behaviors. Furthermore, the negative consequences of these behaviors can intensify feelings of guilt and shame, which, in turn, reinforce the use of ineffective emotion regulation strategies, such as avoidance and suppression (Weiss et al., 2015). The significance of guilt and shame has been highlighted in other studies, which suggest that these emotions, particularly when tied to self-identification with personal failures and feelings of self-hatred are associated with an increased risk of relapse during recovery (Uslaner et al., 1999). Individuals with substance use disorders often suppress unwanted thoughts in an attempt to alleviate these emotionally distressing states, yet research has shown that thought suppression is positively correlated with substance cravings and relapse episodes (Garland et al., 2012; Smith-Russell & Bowen, 2023).) Thought suppression is widely recognized as a maladaptive coping strategy (Baumeister, 2003; Najmi & Wegner, 2008; Petkus et al., 2012). Specifically, studies indicate that the effort required to suppress unwanted thoughts depletes cognitive and emotional resources necessary for more adaptive strategies, such as reinterpreting problematic situations, thereby restricting the range of available emotional responses (Baumeister, 2003; Smith-Russell & Bowen, 2023).

Further supporting the role of memory in emotion regulation, Teasdale and Barnard (1993) examined how autobiographical memory influences the generation and maintenance of negative emotions. They found that memories of autobiographical events are more easily and accurately recalled when the emotional tone of the event matches the individual’s current mood. These findings suggest that certain aspects of negative thinking may arise from depressive moods, which selectively distort memory access, making negative information more likely to be retrieved and used than positive information.

Risky behaviors, such as substance use, often provide immediate relief, making individuals more likely to engage in these behaviors in the future. Over time, this pattern contributes to the development of cognitive frameworks that hinder the adoption of healthy emotion regulation strategies (Weiss et al., 2015). Consequently, individuals often develop rigid perspectives on managing psychological discomfort (Fischer et al., 2005), which may perpetuate reliance on substance use as a primary coping mechanism when adaptive alternatives are unavailable. This aligns with Khantzian’s (1997) self-medication theory, which posits that substance use serves as an attempt to alleviate the negative effects of traumatic experiences. In this context, individuals may turn to substances as a means of numbing emotional pain when they lack more constructive strategies for emotional regulation. In contrast, cultivating a self-compassionate approach may enhance the regulation of emotional responses to perceived threats by promoting consciousawareness, distress tolerance, and the expression of unpleasant emotions (Gilbert, 2014).

In line with this, self-compassion can serve as a valuable tool by shaping how individuals encode and store their emotional experiences in memory, enabling them to process these experiences without an intensified negative charge (Diedrich et al., 2016; Teasdale & Barnard, 1993). Moreover, self-compassion entails adopting a supportive attitude towards oneself, which disrupts self-criticism and encourages motivation to actively process emotional experiences (Diedrich et al., 2016). This function of self-compassion may be particularly beneficial for individuals with substance use disorders, who often lack motivation to engage in active problem-solving. Furthermore, research suggests that the positive effects of self-compassion remain stable despite increases in depressive mood or other negative emotional states compared to other coping strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal (Berking & Whitley, 2014; Diedrich et al., 2014; Hein & Singer, 2008). Neff (2012) attributes this phenomenon to the inherent human desire to be happy and free from self-punishment. The greater the pain, the greater the discrepancy between an unpleasant state and a desired positive emotional state. This disparity can intensify an individual’s motivation to adopt a self-compassionate stance as a means of alleviating suffering (Diedrich et al., 2016; K. D. Neff, 2012). Preliminary evidence supporting this hypothesis comes from Diedrich et al. (2014), who found that self-compassion practices were less effective at reducing mild to moderate depressive moods but significantly more effective at alleviating severe depressive symptoms. Collectively, this evidence underscores the need for interventions that address emotional regulation deficits as part of addiction recovery.

Regarding unpleasant emotional states such as depression, anxiety, and stress, converging findings from international epidemiological and clinical studies have shown that substance use disorders are frequently associated with depression and anxiety disorders (Beaufort et al., 2017). Moreover, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress have been identified as mediators in the relationship between substance use disorders and emotional regulation difficulties (Chen, 2019). Specifically, Mohamed et al. (2020) found that 80% of participants with substance use disorders reported moderate to high levels of anxiety, while 72% experienced moderate to high levels of depression. These findings are further supported by Price et al. (2019), who found a positive correlation between high levels of emotional regulation difficulties and symptoms of depression and anxiety among substance users. In addition to serving as risk factors for substance use disorders, heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and stress have been shown to exacerbate emotional dysregulation, further reinforcing maladaptive coping mechanisms (Bruneau et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2019). These findings not only help identify risk factors for the development of substance use disorders but also underscore the critical role of emotions and the mechanisms individuals employ to process them.

Given the well-documented link between emotional dysregulation, psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) and substance use, there is a growing need for interventions that not only address maladaptive coping strategies but also cultivate psychological resilience. In this regard, self-compassion has emerged as a promising approach, offering an alternative pathway to emotion regulation that may support long-term recovery and relapse prevention. Programs designed to enhance self-compassion have been shown to reduce the risk of relapse. Abdoli et al. (2021) conducted a study on the effects of a self-compassion training program on substance use cravings. The results showed that cravings decreased while self-efficacy levels increased, with participants reporting feeling more capable of handling stressful situations. Similarly, Carlyle et al. (2019) highlighted the therapeutic potential of a brief compassion focused therapy, demonstrating a negative correlation between self-compassion and the risk of developing substance use disorders. These findings underscore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing self-criticism and promoting non-judgmental acceptance of emotional experiences.

Although the effectiveness of these programs has not been thoroughly evaluated in populations with substance use disorders, the negative correlation between self-compassion and key risk factors for these disorders (e.g., emotional dysregulation, inadequate self-care, anxiety, and depression) highlights the potential of self-compassion to support addiction recovery and prevent relapse (Phelps et al., 2018).

In summary, previous studies have shown that self-compassion, emotion regulation deficits, and negative emotional states, such as depression, anxiety and stress, are interconnected and appear to predict the development of substance use disorders.

Some theoretical frameworks, particularly within psychoanalysis, conceptualize addiction as a substitute action, suggesting that a more direct response to one’s feelings of helplessness and frustration may seem unattainable. possible (Fetting, 2011). In other words, individuals may feel that substance use is their only viable response to stress. Addiction, in this sense, becomes a maladaptive coping mechanism, a way for individuals to distract themselves from unresolved emotional pain or helplessness. This cycle reinforces itself, as the temporary relief provided by substances becomes the only perceived solution to inner turmoil

Disrupting the cycle of addiction requires individuals to cultivate healthier ways of relating to their emotional experiences. Self-compassion practices invite individuals to reconsider this substitute reaction and adopt healthier, more direct responses, such as understanding and accepting feelings of vulnerability without resorting to self-criticism (Krentzman, 2013; K. D. Neff, 2003). Khantzian (1997) posits that individuals with substance dependence act out their unprocessed emotions through addictive behaviors, enabling them to avoid intense discomfort arising from their unexplored emotional world. Within this theoretical framework, individuals struggling with substance dependence do not engage in substance use as a means of escaping life, but rather as an attempt to construct a viable existential space—albeit one fundamentally structured by the nature of addiction (Fetting, 2011).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship among self-compassion, emotion regulation difficulties, psychological distress (depression, anxiety, and stress), and thought suppression among individuals with substance use disorders within the Greek population.

The significance of this study lies in its exploration of self-compassion as a potential transformative approach to preventing and addressing challenges faced by individuals with substance use disorders. While emerging research has demonstrated the construct’s potential to enhance emotional well-being, its mediating role in substance use contexts remains largely unexamined. By investigating the predictive and mediating functions of self-compassion in the recovery process, this research aims to contribute a more nuanced understanding of its universal and culture-specific applications.

Existing literature suggests that self-compassion offers a promising alternative to the emotional turmoil caused by unprocessed, distressing emotions. By elucidating the relationship between self-compassion and risk factors for substance use disorders, this study seeks to inform potential innovative strategies for addiction recovery.

This study aims to examine a) the relationship between self-compassion, depression, anxiety and stress, difficulties in emotion regulation, and thought suppression, b) the predictive relationship between difficulties in emotion regulation, depression, anxiety and stress, and thought suppression, and c) the mediating role of self-compassion in the aforementioned predictive relationships.

Method

Participants

The study sample consisted of 150 individuals (111 men, 74%; 39 women, 26%), aged 30–71 years (M = 47.75, SD = 8.29), enrolled in a rehabilitation program at the Hellenic Organization Against Drugs (OKANA) in Attica, Greece. All participants had a history of polysubstance use (including cannabinoids, opioids, stimulants) undergoing opioid substitution therapy with methadone or buprenorphine at OKANA’s Integrated Treatment

The study did not differentiate participants based on their substitution medication, as existing research suggests comparable psychological outcomes for both treatments. Both methadone and buprenorphine have been shown to effectively enhance emotional regulation, cognitive function, and overall psychological well-being among individuals with substance use disorders (Maremmani et al., 2011; Nikraftar et al., 2021). By not stratifying participants based on medication, this study sought to explore self-compassion as a universal psychological construct, ensuring the generalizability of the findings across individuals undergoing opioid substitution therapy.

To determine the required sample size, an a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 software, with parameters set at an effect size of f² = 0.15 (medium effect size), an alpha level of 0.05, a power of 0.95, and three predictors for linear multiple regression analysis. The analysis recommended a minimum sample size of 119 participants; however, to account for potential data loss and to ensure sufficient power to detect smaller effects, the sample size was increased to 150 participants.

The inclusion criteria required participants to be at least 18 years old and have a sufficient understanding of the Greek language to comprehend the questionnaires. Individuals who did not meet these criteria were excluded from the study.

Participants’ ages ranged widely, from 30 to 71 years, which was deemed appropriate given evidence that self-compassion serves as a stable and protective psychological construct across life stages. Specifically, previous research suggests that self-compassion remains reliable and effective in promoting emotional well-being regardless of age (Phillips & Ferguson, 2013).

Measures

Self-Compassion Scale

Self-compassion was assessed using the Self-Compassion Scale (Karakasidou et al., 2017; Mantzios et al., 2015; K. D. Neff, 2003). The scale consists of 26 items that measure three positive components of self-compassion: self-kindness, mindfulness, and common humanity, as well as their three opposing dimensions: self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification. Responses are measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Almost Never) to 5 (Almost Always). Items 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 11, 13, 16, 18, 20, 21, 24, and 25 were reverse-coded before calculating the total score. The Self-Compassion Scale has consistently demonstrated strong validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability across diverse populations (K. D. Neff et al., 2019), rendering it a reliable tool.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – (DERS-18)

The short version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) was used to assess challenges in emotion regulation. This 18-item version evaluates six dimensions: (a) lack of awareness of emotions, (b) lack of clarity regarding emotions, (c) difficulties in engaging in goal-directed behavior, (d) difficulties in controlling impulses, (e) non-acceptance of emotional responses, and (f) challenges in accessing emotion regulation strategies. Participants rated their responses on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Almost Never) to 5 (Almost Always). The item scores were aggregated summed to calculate the total scale score. Items 2, 4, and 6 were reverse-coded before calculating the total score. The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-18 (DERS-18) was selected for this study due to its robust psychometric properties, brevity, and alignment with the focus on multidimensional emotional dysregulation. Comprising only 18 items, the DERS-18 provides a comprehensive assessment of emotional dysregulation across six key domains while minimizing the response burden. This reduction in length makes the scale particularly advantageous for the study’s target population, who may encounter difficulties in completing longer assessments due to emotional or cognitive challenges. (Gouveia et al., 2022; Gratz & Roemer, 2004).

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21)

Depression, anxiety, and stress were assessed using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21), which consists of 21 items divided into three subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress. Responses are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Did not apply to me at all to 3 = Applied to me very much or most of the time). DASS-21 was selected due to its well-established reliability, concise design, and ability to measure three interconnected yet distinct aspects of psychological distress. Furthermore, its comprehensive approach to emotional distress aligns well with the focus of the study. (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Lyrakos et al., 2011).

White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI)

White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI) was used to assess thought suppression. This 15-item scale measures thought suppression on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree). WBSI in this study is directly aligned with its primary focus on thought suppression as a core variable. WBSI was specifically designed to measure chronic thought suppression and demonstrates strong psychometric properties, including high internal consistency and temporal stability, making it a reliable instrument across diverse populations. Furthermore, its theoretical foundation in the paradoxical effects of suppression renders it particularly relevant for studying maladaptive cognitive processes frequently encountered in individuals with substance use disorders (Wegner & Zanakos, 1994).

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each of the four scales based on responses from the sample of 150 participants in this study. The results demonstrated strong internal consistency across all measures: Self-Compassion (a = .88); Difficulties in Emotion Regulation (a = .82); Depression, Anxiety, and Stress (a = .92); White Bear Suppression (a = .86).

Procedure

Participants were recruited from OKANA rehabilitation units in Attica, Greece, between October 2023 and January 2024. Recruitment staff at each unit, who had been briefed on the inclusion criteria, approached eligible beneficiaries and invited them to participate. Those who expressed interest were informed about the study and provided written informed consent.

Upon consent, participants were escorted to a designated private space, where the researcher explained the study’s objectives, voluntary nature, and confidentiality procedures. The researcher remained available to address any questions or concerns throughout the administration process.

The study involved completing four self-report questionnaires, which required approximately 20–25 minutes for completion. Data collection adhered to ethical standards, as approval was obtained from OKANA’s Research Department, following the guidelines of the British Psychological Society (BPS, 2021). Participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without consequences and were assured that non-participation would not affect their treatment.

To protect personal data, a pseudonymization process was implemented. Each participant selected a personal code, which was documented on the consent form. All data were stored on a password-protected computer, accessible only to the researcher and the supervising professor.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 25) and Hayes’ PROCESS macro for mediation analysis. Normality assumptions were tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and non-normal variables were analyzed using bootstrapping methods (1,000 samples). Stepwise regression was used to identify significant predictors.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Participants demonstrated moderate levels of self-compassion, emotion regulation difficulties, psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress), and thought suppression. Table 1 provides an overview of means, standard deviations, and reliability coefficients for all measures.

Correlation Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test indicated non-normal distributions for depression, anxiety, and stress (W = .97, p = .002) as well as thought suppression (W = .97, p = .001). Consequently, Spearman’s rho was used for correlation analysis. Results revealed significant negative correlations between self-compassion and the following variables: emotion regulation difficulties (rs = −.55, p < .001), psychological distress (rs = −.53, p < .001), and thought suppression (rs = −.43, p < .001). These results suggest that higher self-compassion is associated with reduced emotional dysregulation, distress, and thought suppression (see Table 2).

Regression Analysis

To investigate the predictive relationships among self-compassion, difficulties in emotion regulation, depression, anxiety and stress, and thought suppression, the stepwise regression method was applied. This analytical method was deemed the most suitable for exploring potential predictive relationships among the aforementioned variables while minimizing the subjective involvement of the researcher, as the inclusion or exclusion of variables from the model was determined based on mathematical criteria.

Initially, the assumptions of normality, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity were tested. The results indicated that the assumptions of homoscedasticity and multicollinearity were not violated (see Tables 3 and 4 for Tolerance and VIF). The assumption of independence of errors was assessed using the Durbin-Watson statistic, which showed that this assumption was not violated for the first predictive model (Durbin-Watson = 2.18) and for the second predictive model (Durbin-Watson = 2.45). While the normality assumption was not met for the variable psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress), and thought suppression, the validity of stepwise regression depends primarily on the normality of the residuals. The normality of the distribution of errors was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The results indicated that the residuals for the predictive model of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, and stress) followed a normal distribution (D = 0.049, p > .05). In the predictive model of thought suppression, the residuals did not conform to a normal distribution (D = 0.079, p < .05). Consequently, multiple stepwise regression was initially conducted to identify the best predictive model for the variable thought suppression. Subsequently, the Bootstrap method was applied to the most appropriate predictive model, as derived from the stepwise regression, with the number of samples set at 1,000.

Stepwise Regression with Dependent Variable: Psychological Distress (depression, anxiety, stress)

A stepwise regression analysis was conducted to examine the predictors of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress). The final model explained 45.2% of the variance (R2 = .452, F (3,146) = 40.12, p < .001, indicating a large overall effect size (f2 = 0.83). The predictors included difficulties in emotion regulation (β = .37, p < .001), self-compassion (β = −.23, p = .003), and thought suppression (β = .21, p = .005).

The first model, in which difficulties in emotion regulation were included as a predictor, explained 37.0% of the variance (R2 = .37, F(1,148) = 87.06, p < .001), representing a large effect size (f2 = 0.59). This variable significantly predicted psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (β = .61, p < .001).

The inclusion of self-compassion in the second step increased the explained variance to 42.1% (R2 = .42, ΔR2 = 0.05, F(2,147) = 53.49, p < .001), resulting in a medium effect (f2 = 0.09). Difficulties in emotion regulation (β = .46, p < .001) and self-compassion (β = −.27, p < .001) were both significant predictors at this step (see table 3).

Stepwise Regression with Dependent Variable: Thought Suppression

A stepwise regression analysis was conducted to investigate the predictors of thought suppression. The final model explained 33.1% of the variance in thought suppression (R2 = .33, F(2,147) = 36.35, p < .001), indicating a medium-to-large overall effect size (f2 = 0.49). The predictors included difficulties in emotion regulation (β = .35, p < .001), psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (β = .29, p = .001).

The first model, in which difficulties in emotion regulation were included as a predictor, explained 27.7% of the variance (R2 = .28), representing a large effect size (f2 = 0.38). This variable significantly predicted thought suppression (β = .53, p < .001).

The inclusion of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) in the second step increased the explained variance to 33.1% (ΔR2 = .05, p = .001), resulting in a small effect size for this predictor (f2 = 0.08). Difficulties in emotion regulation (β = .35, p < .001) and psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (β = .29, p = .001) were both significant predictors at this step (step 4).

Due to the non-normal distribution of the residuals, the Bootstrap method was applied to the above model to draw more reliable conclusions. The results are presented in Table 5, which includes confidence intervals and standard errors based on 1,000 bootstrap samples.

Mediation Analysis

To address the final research question, we examined the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between difficulties in emotion regulation (predictor) and psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (outcome). The mediation effect was statistically significant. Difficulties in emotion regulation significantly predicted self-compassion (b = −0.75, 95% CI [−0.93, −0.57], t = −8.24, p < .001), accounting for 31.44% of the variance (R² = .31), F(1, 15) = 67.88, p < .001. In the presence of self-compassion, difficulties in emotion regulation also significantly predicted psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (b = 0.51, 95% CI [0.34, 0.67]), while self-compassion had a significant negative effect on psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (b = −0.23, 95% CI [−0.35, −0.10], t = −3.60, p < .001), with the model explaining 42.12% of the variance (R² = .42). In the absence of self-compassion, difficulties in emotion regulation remained a significant predictor of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (b = 0.67, 95% CI [0.53, 0.82], t = 9.33, p < .001), explaining 37.04% of the variance (R² = .37), F(1, 148) = 87.06, p < .001. Additionally, the indirect effect of difficulties in emotion regulation on psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) via self-compassion was significant (b = 0.17, 95% BCa [0.07, 0.28], p < .05), with a standardized indirect effect of β = .15, 95% BCa CI [0.065, 0.255] (see Figure 1).

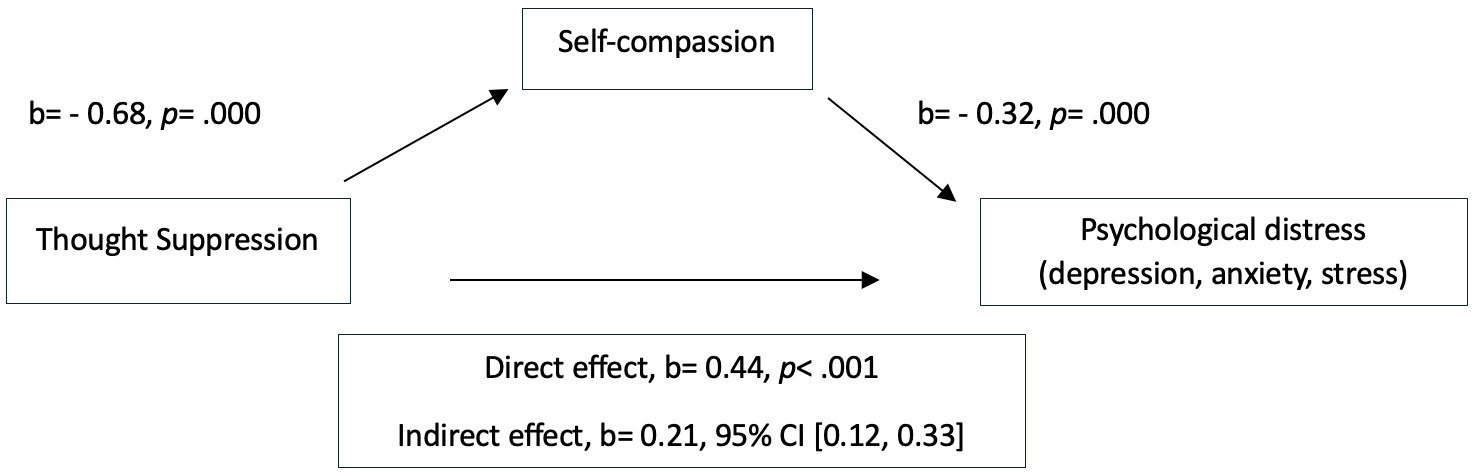

Next, the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between thought suppression (predictor) and psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (outcome) was examined. Thought suppression significantly predicted self-compassion, F(1, 148) = 34.38, p < .001, b = −0.68, 95% CI [−0.91, −0.45], explaining 18.85% of the variance (R² = .19). In the presence of self-compassion, thought suppression significantly predicted psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (b = 0.44, 95% CI [0.25, 0.63]). Additionally, self-compassion had a significant negative effect on psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) (b = −0.32, 95% CI [−0.44, −0.20], p < .001), with the model explaining 37.19% of the variance (R² = .37). In the absence of self-compassion, thought suppression significantly predicted psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress), F (1, 148) = 50.44, p < .001, b = 0.65, 95% CI [0.47, 0.84], explaining 25.42% of the variance (R² = .25). The indirect effect of thought suppression on psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) via self-compassion was significant (b = 0.21, 95% BCa [0.12, 0.33]), with a standardized indirect effect of β = .166, 95% BCa CI [0.092, 0.250] (see Figure 2).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the predictive and mediating role of self-compassion in the relationships among emotion regulation difficulties, psychological distress (depression, anxiety, and stress), and thought suppression among individuals with substance use disorders.

Participants reported moderate levels of self-compassion, emotion regulation difficulties, psychological distress (depression, anxiety, and stress), and thought suppression. While it would be expected for individuals with substance use disorders to exhibit low levels of self-compassion and high levels of emotional dysregulation, psychological distress, and thought suppression, these moderate findings may reflect the influence of ongoing detoxification. In other words, engagement in the detoxification program along with the psychological support provided by OKANA may have gradually enhanced participants’ emotional awareness and reinforced their capacity to regulate distressing thoughts and feelings. As Fetting (2011) and Khantzian (1997) suggest, the detoxification process can play a key role in stabilizing psychological well-being, potentially explaining the shift from expected low self-compassion levels.

The findings revealed a significant negative correlation between self-compassion and emotion regulation difficulties, psychological distress (depression, anxiety, and stress), and thought suppression. These results reinforce prior research on the protective role of self-compassion in psychological well-being by highlighting its association with improved emotion regulation and reduced reliance on maladaptive coping strategies such as thought suppression (Diedrich et al., 2016; Eichholz et al., 2020; K. D. Neff et al., 2007; Scoglio et al., 2018; Vettese et al., 2011). Empirical findings further demonstrate that self-compassion is strongly associated with lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (Joeng & Turner, 2015; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012; K. D. Neff, 2003). Han and Kim’s (2023) meta-analysis shows that self-compassion interventions can effectively diminish these symptoms through mechanisms such as reduced rumination and enhanced self-care motivation. Consistent with these findings, Diedrich et al. (2016) in a study examining individuals with major depressive disorder found that employing self-compassion prior to explicit cognitive reappraisal significantly improved participants’ ability to regulate depressed mood. These findings suggest that self-compassion plays a significant role in enhancing emotion regulation capacities not only by directly facilitating emotion regulation but also by promoting the effective use of other adaptive coping strategies.

This study further expands on the role of thought suppression, revealing how this maladaptive strategy is intricately linked to emotional regulation difficulties. Thought suppression has been shown to hinder emotional awareness and problem-solving capacities, which, in turn, increase vulnerability to impulsive behaviors and psychological distress (Efrati et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2021; Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000). These findings highlight the distinct pathways through which maladaptive strategies, such as thought suppression, and adaptive strategies, such as self-compassion, influence mental health outcomes (Aldao et al., 2010; Spada et al., 2015).

Furthermore, these findings align with prior research indicating that emotion regulation difficulties, psychological distress, and thought suppression are closely interconnected, reinforcing their cumulative impact on mental health (Aldao & Dixon-Gordon, 2014; Hofmann et al., 2012; Jaso et al., 2020; Mennin, 2004). Dysfunctional strategies, such as rumination and emotional avoidance, have been shown to exacerbate psychological distress, whereas adaptive strategies—such as mindfulness, a fundamental component of self-compassion—can mitigate depression and physiological disease (Compare et al., 2014; Singer & Dobson, 2009). Addressing these intertwined factors is critical, as emotional dysregulation, along with depression, anxiety, and stress often reinforce one another, creating a cyclical pattern that may contribute to substance use behaviors (Prosek et al., 2018; Smith-Russell & Bowen, 2023; Weiss et al., 2022).

Regarding the second research question, self-compassion emerged as a significant predictor of lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. In contrast, emotion regulation difficulties and thought suppression were associated with higher levels of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, and stress). These findings are consistent with previous research underscoring the role of self-compassion as a counterbalance to self-critical thoughts and avoidance behaviors (K. Neff & Tirch, 2013). One possible explanation involves the role of the affect-generating system—a set of neural and emotional mechanisms responsible for producing and regulating emotional responses—which has limited cognitive and emotional processing capacity (Teasdale & Barnard, 1993). According to Diedrich et al. (2016), activating this system through self-compassionate responses, such as mindful acceptance and kindness, may consume cognitive and emotional resources that would otherwise be allocated to maladaptive patterns like rumination or harsh self-criticism. In this way, self-compassion may displace depressive emotional states, such as hopelessness and perceived isolation.

Furthermore, self-compassion may promote emotional resilience by fostering a stable sense of self-worth and internal sense of safety during times of distress, thereby reducing the impact of stressful events and facilitating the use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies (Zessin et al., 2015). Additionally, the capacity of self-compassion to cultivate a sense of common humanity may mitigate feelings of loneliness and social disconnection, which are often implicated in mood disorders (K. D. Neff, 2003). These findings collectively underscore the potential of self-compassion as a key intervention target in reducing emotional distress among individuals with substance use disorders.

The final research question explored whether self-compassion mediated the predictive relationships among the study’s variables. Results showed that self-compassion partially mediates the relationship between psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) and both emotion dysregulation and thought suppression. This suggests that while greater psychological distress is linked to difficulties in emotional regulation and an increased reliance on thought suppression, self-compassion may buffer these associations to some extent.

These findings align with previous research demonstrating the mediating role of self-compassion in related psychological processes. For instance, Tao et al. (2021) found that self-compassion mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and adult depression, suggesting that self-compassion may help alleviate the long-term psychological consequences of early adversity. Similarly, Vettese et al. (2011) found that self-compassion mediates the relationship between childhood abuse and emotional dysregulation among adults seeking treatment for substance use, highlighting its potential role in mitigating emotion regulation difficulties associated with adverse experiences. Additionally, Zhang et al. (2018) demonstrated that self-compassion mediates the association between shame and depression, two factors frequently associated with substance use disorders. Further supporting the protective role of self-compassion, Stutts et al. (2018), in a longitudinal study, demonstrated that self-compassion buffers against the adverse effects of stress on symptoms of depression and anxiety, with these effects maintained over a six-month period.

Given the observed associations between self-compassion, psychological distress, and maladaptive coping strategies, these findings suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing self-compassion could help mitigate the negative impact of depression, anxiety, stress on emotional dysregulation. Previous research demonstrated that individuals who engage in self-compassion practices report enhanced social connections, greater life satisfaction, reduced anxiety and depression, reduced tendencies toward rumination and reduced feelings of isolation and loneliness (Hosseinbor et al., 2014; K. D. Neff, 2003; K. D. Neff et al., 2007; Smeets et al., 2014). Notably, these psychological and interpersonal difficulties are frequently observed among individuals with substance use disorders. Consequently, self-compassion emerges as a potentially critical intervention strategy, offering a therapeutic approach that directly addresses the multifaceted psychological vulnerabilities endemic to substance use disorders (Chen, 2019; Suh et al., 2008).

While the present study highlights the importance of self-compassion in mitigating psychological distress and maladaptive coping mechanisms, it is essential to consider the broader social and relational factors that influence these processes. Family dynamics and gender are significant external factors that can shape the course of addiction and recovery (Harris et al., 2022). Research highlights that adverse family experiences, such as conflict, neglect, or criticism, contribute to the onset and persistence of substance use disorders, whereas supportive family relationships promote positive recovery outcomes (Boyer et al., 2020). These relational dynamics not only affect the trajectory of addiction but also impact an individual’s ability to cultivate self-compassion, which is often rooted in familial interactions (Godleski & Leonard, 2019; Henry et al., 2003) and shaped further by experiences within romantic partnerships (Fairbairn et al., 2018; Rodriguez & Derrick, 2017).

In addition to early relational experiences, gendered dynamics within intimate relationships may further exacerbate vulnerability to substance use. For instance, Giannouli and Ivanova (2019) emphasize the impact of partner dynamics, revealing that dominant partner attitudes are significantly associated with Lesch Type III alcoholism in women—a subtype characterized by alcohol use for mood enhancement. These findings underscore how gendered relational dynamics, including critical or controlling partner behaviors, can undermine emotional resilience and hinder the development of self-compassion. In other words, substance use disorders do not arise in isolation but are significantly influenced by external factors, including familial relationships, societal norms, and environmental stressors. These influences often perpetuate patterns of self-criticism and shame, which self-compassion interventions aim to address.

While self-compassion has demonstrated benefits across genders, emerging evidence suggests that men and women may engage with its components in distinct ways. For instance, Garner et al. (2020) found that mindfulness—a core component of self-compassion—significantly reduced alcohol consumption among men, likely due to its role in alleviating cravings. Conversely, women appeared to benefit more from the facets of self-kindness and common humanity, which were associated with reduced alcohol use and enhanced emotional resilience. These findings emphasize the need for tailored interventions in which mindfulness-based practices may better address the needs of men, while self-kindness and common humanity components could be particularly effective for women. Such approaches demonstrate the adaptability of self-compassion as a therapeutic tool that aligns with gender-specific recovery pathways.

While these gender-specific responses highlight the nuanced nature ways in which self-compassion operates, it is also essential to recognize its broader, universal potential. Despite the profound impact of familial relationships, societal norms, and environmental stressors on substance use disorders, self-compassion has emerged as a universal therapeutic mechanism that can be cultivated regardless of gender or severity of past trauma (Dahm et al., 2015; C. Germer & Neff, 2019; K. D. Neff, 2023), making it particularly valuable for diverse populations in recovery. By addressing internalized patterns of shame and self-criticism—patterns that often stem from these external factors—self-compassion interventions provide significant benefits for individuals across genders and familial contexts. Evidence suggests that self-compassion can buffer against the effects of shame, self-criticism, and emotional dysregulation, which are prevalent among individuals with substance use disorders. Notably, interventions aimed at cultivating self-compassion have demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing psychological distress and enhancing emotional resilience, even among those with a history of childhood trauma or maltreatment (C. K. Germer & Neff, 2015; Sajjadi et al., 2023).

Moreover, studies indicate that self-compassion is a teachable skill that equips individuals with practical tools for reframing negative self-perceptions and enhancing emotional regulation. Although women may initially report lower levels of self-compassion, likely shaped by societal pressures and increased self-criticism -, interventions designed to address these pressures have shown comparable benefits for both men and women. This highlights the versatility of self-compassion as a therapeutic tool capable of bridging gender disparities in recovery outcomes (Chen, 2019; Yarnell et al., 2015). The universality of self-compassion underscores its potential to transcend gendered and relational barriers in addiction trajectories, offering individuals an adaptable framework for recovery.

Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. Future research should adopt longitudinal methods to assess the sustained effects of self-compassion on recovery outcomes. Second, the sample was drawn exclusively from a single treatment organization in Greece, limiting the generalizability of findings. Expanding this research to diverse cultural and treatment contexts would provide more robust conclusions. Lastly, while this study focused on self-reported measures, incorporating objective behavioral and neurobiological assessments (e.g., neuroimaging) could offer deeper insight into the mechanisms underlying self-compassion’s efficacy.

Future Directions

Future research should explore the barriers to adopting self-compassion, such as fears of self-compassion or cultural stigmas surrounding emotional expression (Gilbert et al., 2011). Additionally, examining the interaction between self-compassion and other contextual factors, such as family dynamics or gender-specific experiences, could refine intervention strategies (Boyer et al., 2020). Finally, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) testing self-compassion-based interventions in SUD populations would provide critical evidence for their effectiveness in reducing relapse rates and enhancing psychological well-being.

Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that higher levels of self-compassion are associated with fewer emotional regulation difficulties; lower levels of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress); and a reduced need for thought suppression. Furthermore, self-compassion has emerged as a protective factor that mediates the relationship between psychological challenges. These results build upon previous research by emphasizing the potential of self-compassion to enhance emotional resilience in individuals with substance use disorder. Interventions that incorporate self-compassion training may provide more adaptive coping strategies, helping individuals manage emotional distress and reduce reliance on maladaptive behaviors such as thought suppression. By promoting acceptance and tolerance of difficult emotions, self-compassion interventions offer a promising avenue for reducing relapse and fostering long-term recovery.

Author Note

This research is based on the first author’s master’s thesis, which was conducted at Panteion University.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.